Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Oct-12-2012 22:00

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Oregon Blown Away By the Columbus Day Storm 50 Years Ago Today

Wolf Read special to Salem-News.comOctober 12, 1962 is a day that lives in infamy- in Oregon, anyway.

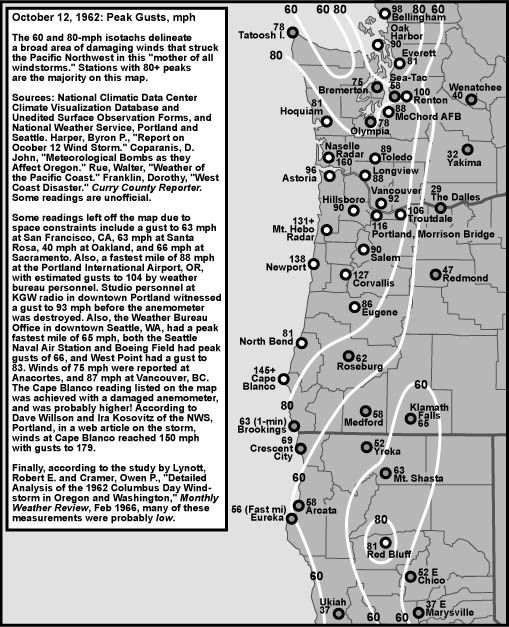

Photos Courtesy of George Taylor, the Oregon Climate Service |

(SALEM) - With little fear of exaggeration, it can be stated that the Columbus Day Storm of 1962 was the most powerful windstorm to strike the Pacific Northwest in the 20th century. Certainly no windstorm since has generated as much widespread devastation as the Big Blow, not even close.

Comparisons of peak gusts, where they can be had, tend to put the Big Blow at the top, but such figures are abstract, and often don't reveal the very reasons why those who lived through the Columbus Day Storm remember it so vividly.

The sudden violence of the wind compelled many people to take cover in their homes or basements, a lasting memory, and the sheer magnitude of destruction, in literally all categories of accounting, puts this storm far above any other.

For example, the northwest Oregon town of Lake Oswego had about 4,000 houses within its borders in 1962--the Columbus Day Storm damaged 70% of these structures [1].

A more typical windstorm might not even harm this many houses within the entire range of its influence. Indeed throughout the Willamette Valley, undamaged homes were the exception, not the rule.

In 1962 dollars, the Columbus Day Storm caused an estimated $230-280 million in damage to property in California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia combined, with $170-200 million happening in Oregon alone [2]. This damage figure is comparable to eastern hurricanes that made landfall in the 1957-1961 time period: Audrey, 1957, $150M, Donna, 1960, $387M, and Carla, 1961, $408M [3].

The "Big Blow" was declared the worst natural disaster of 1962 by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. In terms of timber loss, about 11.2 billion board feet was felled by the Big Blow in Oregon and Washington combined.

In sheer gustiness of wind, as indicated by the ratio of maximum gust speed to sustained wind speed, called the gust factor, the Columbus Day Storm behaved more like a hurricane than a typical midlatitude cyclone [4].

VanBuren Bridge, Corvallis, OR |

The large number of 1,000-year-old plus trees blown down suggests that the Columbus Day Storm may have been the event of the millennium [5], though such inferences are speculative at best.

The Columbus Day Storm was born explosively when the highly degraded extratropical remains of typhoon Freda drifted into a powerful storm formation zone off of northern California and regenerated the ailing cyclone [6]. The extratropical cyclone origin gives the event a unique place among Northwest windstorms, for, as far as is known, this has not happened at any other time in the period of climatological record.

Certainly the remains of dead typhoons have arrived on the Pacific Coast on many occasions since 1950, but few have come ashore as strong storms, and none but the ghostly remains of Freda in 1962 have been spun into a terrific wave cyclone.

The abundant energy that arrived with the tropical system may partly explain the level of violence achieved during the Big Blow. And this tropical influence suggests that the storm of 1962 be placed in its own category.

A lone, dark overachiever whose closest cousins may be those powerful extratropical storms experienced on the East Coast, such as post-landfall hurricane Hazel of 1954. There are other reasons for a unique place in Pacific Northwest climatology, such as pressure tendencies that mirrored fast-moving landfalling systems while the center of the Columbus Day cyclone stayed offshore, as will be discussed in detail in the storm data section, and simply the storm's incredible peak wind velocities.

The Columbus Day Storm struck at a time when many regularly reporting weather stations were operating. This gives the Big Blow a unique place when it is compared to major events that are deeper in the past, such as the 1880 Storm King.

With a large body of good data, the storm can be studied in great detail, from its formation, to its track, and its effects at a wide variety of locations. Of course, many storms have struck during the period of excellent climatological record. Out of all these tempests, the Columbus Day Storm was an event that generally stands far above the others.

TABLE 1 |

It is for the above reasons that the Columbus Day Big Blow is often used as a benchmark for comparing windstorms, as is done at this website. Thus, many facts and figures about the Columbus Day Storm are found on pages dedicated to other windstorms.

However, caution should be used when making certain types of comparisons. As discussed on the December 12, 1995 windstorm page, there are aspects about the Columbus Day Storm that are different from the standard attack from a big cyclone passing northward off of the Pacific Coast.

The Columbus Day cyclone's minimum central pressure of about 960 mb really wasn't that unusual among the other big storms of history [7]. For instance, with a minimum pressure of 954 mb, the December 1995 storm was deeper, as was the November 1981 storm's 958 mb [8]. However, the Columbus Day winds were much stronger than the 1995 and 1981 storms.

The 11-station average peak gust figures used on this website reveal this: 61.4 for December 1995, 65.9 for November 1981, and a screaming 80.5 for Columbus Day 1962 [9]. The Big Blow of 1962 was the only storm to break 70 in the 11-station measure for the 1950-to-present era, and it accomplished this by a large margin!

The Columbus Day Storm is an outlier, a singularity. An event like the Columbus Day Storm probably won't happen again for another 100 years, maybe even 1,000. For some comparisons, the Columbus Day Storm probably should be put in its own category--especially when trying to forecast the peak wind potential of a new cyclogenic bomb based on windstorm climatology.

As Powerful as a Hurricane

Table 1, compares the Columbus Day Storm peak gusts to those of Hurricane Hazel. There is a tendency among weather officials not to do these kinds of comparisons because the two types of storms--midlatitude cyclones and hurricanes--are so different.

There is also the added "taint" from the fact that the Columbus Day Storm was generated in part by entraining the extratropical remains of typhoon Freda, and the news media in some cases suggested that the Columbus Day Storm was Freda.

However, hurricane Hazel, after making landfall near Myrtle Beach, SC, and then shooting northward up the Eastern Seaboard, "degenerated" into a very powerful extratropical cyclone, according to some interpretations of the events in 1954.

So possibly Hazel wasn't a far cry different from the Columbus Day Big Blow--both storms seem to have spent part of their existence in a gray zone between solidly defined hurricanes and midlatitude cyclones, the mark of Nature's disdain for the hard categories often created by humans.

And, indeed, there are plenty of similarities between Hazel and the Columbus Day Storm: both storms had a significant tropical influence, both made landfall in mid-October, the two storms first struck to the south and then veered northward at a fast clip and raced all the way into Canada, they kicked up record wind speeds over a large part of their prospective afflicted coastal strips, and they dumped heavy rains over large regions.

And so, we have the side-by-side comparisons of wind speeds below. This is to remind the reader just how powerful the Columbus Day Storm was, evidence that the Pacific Northwest can be struck by truly severe weather on occasion.

Barograph Charts

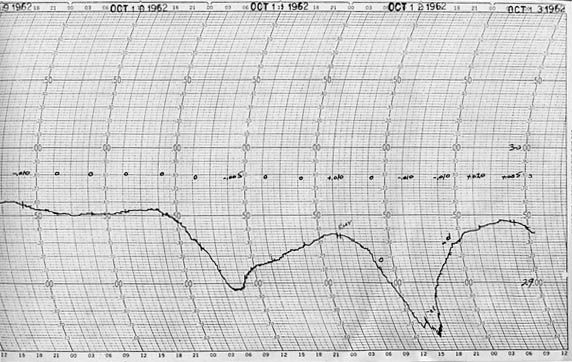

BAROGRAPH TRACE, SALEM, OR |

This is a copy of the actual Columbus Day Storm barograph trace for Salem, barometer elevation 201.3 feet.

The Columbus Day Storm produced the sharp "V" to the right. This trace also shows the fairly strong dip of the October 11th storm to the left center.

For the Columbus Day Storm, note the sharply defined double-dip at the bottom of the "V", a feature was turned up strongly at Willamette Valley stations during this storm.

The initial dip was due to the passage of the storm's leading front. This kind of double-dip signature has appeared in many windstorms, often more weakly than the one below.

Apparently, double-dips didn't get much attention until the Columbus Day Storm's clear examples, and this feature is often remarked upon in scientific literature on the storm of '62.

General Storm Data

Minimum Pressures and Peak Gradients

It appears that Portland's lowest pressure was achieved during the first dip in the double-dip signature shown in the storm, and Eugene and Salem had minimum during the second dip, which accounts for the earlier arrival of pressure minimum at Portland.

For the period 1950 to present, the 11-station average minimum pressure for the Columbus Day Storm, 28.84" (976.6 mb), is second only to the 28.69" (971.6 mb) value achieved during the December 12, 1995 storm.

Among the lowest pressures measured during the October 12, 1962 event was 28.54" (966.5 mb) at Destruction Island, WA, and 28.42" (962.4 mb) from the picket ship MS, off the Northern California coast.

Interestingly, despite the high average tendencies, when individual stations are examined, very few long-standing records were set on Columbus Day 1962.

Only the peak climb values for Medford, Eugene, Salem and Bellingham still stand as records today, and Eugene only because the pressure surge from the February 7, 2002 South Valley Surprise started between the regular observation times, resulting in a +7.5 mb (+0.21") peak reading on the hour (16:54), when indeed a +10.2 mb (+0.30") rise occurred in about 48 minutes (from 16:24 to 17:12).

The high average hourly declension for the Columbus Day Storm is no different. Still-standing records were set at just Astoria and Salem during the Columbus Day Storm.

The storms that produced the higher readings for both pressure fall and climb at the other stations are quite varied. Often the record setter is a cyclone that passed very close to a particular station, and because of this nature, it is almost always a different storm for each station's record.

The list is long and convoluted. For example, there's North Bend. The +8.8 mb (+0.26") surge on Columbus Day of 1962 was incredible--rarely do one-hour pressure rises reach into the eight-mb range in the Pacific Northwest--but it is far short of the truly astounding one-hour surge of +16.6 mb (+0.49") during a landfalling cyclone on November 10, 1975 and +14.2 mb (+0.42") also during another landfalling storm on February 7, 2002.

The 1975 and 2002 storms were very localized to Southwest Oregon. For example, on february 7, 2002, Astoria, at the north end of the state, had a meager +2.4 mb (+0.07") maximum climb out of the event, far short of the +7.7 mb (+0.23") surge seen on Columbus Day 1962, and Astoria's all-time biggest hourly jump of +8.0 mb (+0.24") during the Inauguration Day storm of 1993.

That the Columbus Day Storm set the all-time maximum average pressure tendencies for the 1950-to-present era while not setting most individual station records, reflects on an event that strongly affected the entire region quite uniformly, unlike many of the individual station record-setters.

A Vast Trail of Destruction

Shown below is a copy of the original surface observation form for Corvallis, OR, used for the time period October 10th to October 15th. Weather observations were fairly routine up to 14:00 on October 12th. Then the 15:00 observation was missed, and what followed is quite extraordinary.

Winds at 16:00 had elevated to 60 knots gusting to 85 (69 mph gusting to 98), with a peak gust noted at 110 knots (127 mph)! Just a few moments later, at 16:15, "ABANDONED STATION" is clearly written in the middle of the form.

The next day, it is also noted, "Unreported from 04:00 - 12:00 due power failure and instruments demolished."

SURFACE OBSERVATION, CORVALLIS, OR. |

Like a Hurricane

Many eyewitness accounts suggested that the Columbus Day Storm was like a hurricane. These comments were sometimes made by people who had experienced hurricanes beforehand. Here's a piece of weather data that just about corroborates these claims, from Red Bluff, California: Rainfall 0.41" in 5 minutes, accumulating to 0.98" within 15 minutes, with peak average wind 68 mph (fastest mile), gusts higher, and a temperature around 64 F.

The temperature is slightly cool for a hurricane, and the average winds weren't quite at the 75 mph cutoff for hurricane status (plus the highest winds occurred before the heavy rain event), but the figures aren't too far off the mark, especially with rainfall rates at 8.20"/hr for that first 5-minute period.

A person witnessing the conditions generated by the Columbus Day Storm would have compelling evidence to make the claim "Like a hurricane."

References:

[1] Oregon City Enterprise-Courier, October 15, 1962, p. 9.

[2] Damage estimates are from may sources, including, (1) Lucia, E., The Big Blow, p 64. (2) Phillips, Earl L, "Columbus Day Storm in Washington October 12, 1962," Weather Bureau State Climatologist Office, no completion date given. (3) Sumner, Howard C, "Pacific Coast storm, October 11-13, 1962," Weekly Weather and Crop Bulletin, National Summary, U.S. Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau,Vol XLIX, No. 44, October 29, 1962. Other figures cited after this line also from these sources, unless indicated otherwise.

[3] Simpson, R. H., Riehl, H., The Hurricane and its Impact, p. 21.

[4] See, Simpson, R. H., Riehl, H., The Hurricane and its Impact, p. 204-212, for a more thorough explanation of gust factor and how it relates to hurricanes and other types of storms. Basically, a typical midlatitude storm might generate gusts about 1.3 times that of the sustained wind speed, and a hurricane's gusts often reach 1.5 times the sustained windspeed.

Though many locations saw gusts in the 1.3 range in the Columbus Day Storm, there were those with significantly higher ratios: take Bellingham, WA, for instance, which reported at 23:58 PST sustained winds of 58 mph with gusts to 98. That's a ratio of over 1.6.

[5] Oregonian, November 17, 1981, suggested in the Editorials Section, page B4.

[6] Discussion on the storm's tropical connection can be found in several references, including: (1) Franklin, Dorothy, "West Coast Disaster," in the technical discussion, "The Terrible Tempest of the Twelfth." (2) Lynott, Robert E., Cramer Owen P, "Detailed analysis of the 1962 Columbus Day windstorm in Oregon and Washington," Monthly Weather Review, February 1966, Page 110.

[7] Minimum central pressure for the Columbus Day Storm is from Lynott, Robert E., Cramer Owen P, "Detailed analysis of the 1962 Columbus Day windstorm in Oregon and Washington," Monthly Weather Review, February 1966.

[8] Minimum central pressures for the November 1981 and December 1995 storms are from Willson, Dave, Kosovitz, Ira, "Columbus Day 1962 Storm," online summary provided by the National Weather Service, Portland, aired on October 2002.

[9] Peak gust data is from the National Climatic Data Center, unedited surface observation forms for Aracta, Medford, North Bend, Eugene, Salem, Portland, Astoria, Olympia, Sea-Tac, Tatoosh Island and Bellingham, October 12, 1962 (forms WBAN 10A and 10B).

Originally published September 16, 2001: http://www.climate.washington.edu/stormking/October1962.html

Articles for October 11, 2012 | Articles for October 12, 2012 | Articles for October 13, 2012

Salem-News.com:

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

John October 14, 2012 8:06 am (Pacific time)

Nice set of data

[Return to Top]©2025 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.