Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Nov-22-2010 03:00

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

My Lai Survivor Disappointed in Calley's 'Terse Apology' for War Crimes Atrocities

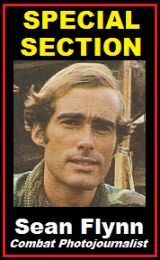

Tim King Salem-News.comIncludes Duc Tran Van's open letter to William Calley.

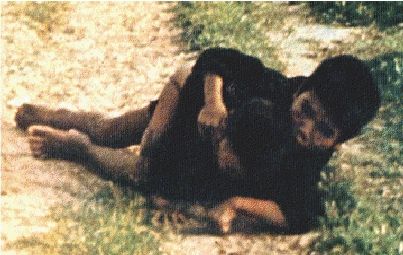

Ha Thi Qui, Ba Nhieu and Tran Van Duc in My Lai (Photo courtesy Tran Van Duc) |

(SALEM, Ore.) - It is a dubious honor that a photo from an article I wrote about the 40th anniversary of the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam, is one of the top picks on Google Images under this tragic subject.

Lt. William Calley |

I have received a great deal of interesting email as a result of that article, titled My Lai Massacre in Vietnam Happened 40 Years Ago this Weekend, and I'm recently humbled by contact from My Lai survivor Duc Tran Van, who was a seven-year old boy in his village when American soldiers almost completely decimated My Lai's entire population.

Today Duc Tran Van has a few things to say to former Army Lt. William Calley. He seeks to express his dismay over what he referred to as a terse apology Calley issued for the massacre at My Lai; the village name is Calley's legacy, along with his commander, Major Ernest Medina.

Publishing the words of Duc Tran Van is a solemn honor, as it was to publish our Writer Chuck Palazzo's article, The 42nd Anniversary of the Massacre at My Lai last May.

A resident of Remscheid, Germany, Duc Tran Van lost a great deal the day the Army came to My Lai.

Photo of Duc Tran Van's mother's body was misidentified in the past |

A widely published photograph of a young woman laying on the ground in a blue shirt, with a bullet through her head, is his mother.

One can only imagine the horror this 1968 event represents to the few who survived it.

Nothing can restore the real balance of this place, but hearts are heavy in many Americans over the terrible side of this war, and they do what they can to counter the actions of a few who do not fairly represent the typical Vietnam Combat Veteran. As horrific as that act was, there has been a great deal of atonement from Americans who fought in the war.

Chuck Palazzo, located in Danang, Vietnam today, where he was based during the war as a US Marine, is one of those Americans who gives back what he can. He employees indigenous people and constantly invests his energy in the local economy. While covering the 42nd anniversary of the tragedy, he visited and hugged, laughed and cried with these special people who somehow survived the guns that day.

Many, if not most of the men in 'Charlie Company' under the command of Lt. William Calley, have died since the end of the war, many by committing suicide.

The defenders of Calley - then and now, stick up for men who committed vicious acts of rape and degrading cruelty toward human beings that is the kind that could never be excused.

It was purely opportunistic.

A close friend of mine who is an Army Lt. Colonel, once told me it is extremely clear in the training of a US Army officer, that there is never a time when civilian non combatants can legally be lined up and abused, then slaughtered in cold blood, never a time.

Lowered Entrance Requirements

War is Hell, especially when the US Congress chooses to lower the qualification level of recruits. A large number of the My Lai soldiers were 'Category 4' ASVAB entrants. They would normally have been denied entry over extremely low intelligence, mental problems, criminal pasts and other issues. Congress lowered the bar, and then came My Lai. President George W. Bush did the same thing during the peak of the war on Iraq.

It seems logical that keeping this history in front of people would possibly prevent it from recurring, but Americans have never been good about discussing My Lai. There are still many who stick up for Calley, it is unimaginable. Today William Calley lives a good, comfortable life in Georgia. I can only imagine the visitors he has had over the years.

Here is Duc Tran Van's open letter to William Calley:

Duc Tran Van

Remscheid, Germany

Dear: William Calley

I’m Duc Tran Van, living here in Germany since 1983. Almost one month ago, I’ve read from your newspaper about “William Calley”. He said, he felt sorry about the “My Lai massacre”, where over 504 People killed.

Tran Van Duc (1962) and Tran Thi Ha(1967) –Ronald Haeberle 16.3.1968.

We are survivors from the “My Lai massacre” at March 16 1968 in Thap Canh.

At this time, I was 7, my older sister 9 years old and my youngest sister 14 months. During the gunfire my mother protected me, and my little sister in her fall, by lying beneath us. When the gunfire ended, and the Americans were away, my mother told me to run away immediately.

Duc protects infant brother - My Lai

Despite her injuries in her leg and stomach, my mother has dragged herself to the street to see us running away. So she had to see her other two daughters lying dead on the other roadside. I ran away from this place, carrying my sister. At about 2km away, I heard a helicopter. I threw myself with my sister on the ground, and we played dead. The helicopter flew so low that I could clearly see the photographer. After the helicopter was gone, I ran with my sister again. Approximately 4 hours later, we arrived Son Hoi. Interrupted by repeatedly having to hide, every time a helicopter noise was heard, and also having rests from the strain of carrying my 14 months old sister.

The next morning my older sister also arrived there. She survived the massacre by about 15 minutes of waiting under corpses in the rice field.

Only in 1975, I find out that my mother, shortly after I ran away with my sister, was killed by headshot, through the press photograph of my mother in the "My Lai Memorial". (As I previously said, this photo is exhibited there under a false identity)

It was extremely hard in the following time for us to survive without parents and without any assistance.

I want to write to Mr. William Calley! He must know what his actions did to our families! And what it has done to the village of My Lai, to murder 504 people, mothers, children and elderly people.

For this few (only a handful) of survivors that continued to live, it was definitely very hard. Especially there were only some children and a few elderly people. A terse "apology", after over 40 years for the total destruction, not only the people but also their homeland, is simply a disappointment!

PS:

Enclosed I’m sending you my recollections of the event, especially from this day, with several press, even from me and my family members, with corrections of the identity of the persons depicted, in Vietnamese language. I would ask you, if it is possible for you, to translate them into English, and also to send it to Mr. Calley.

Yours sincerely,

Duc Tran Van

By David Calleja September 7, 2010

I was born Tran Van Duc in 1962, the third child and oldest son in my family. My mother sold food at a local market and my father was a tailor, selling clothes and western medicine. He had previously been held captive by the government, and as a result we were all under constant surveillance, reporting to authorities daily.

My lai massacre in pictures, U.S army photographers captured the events of |

We had a large house near Son My Market. On one side, our neighbor owned a lot of coconuts and stored them in his yard, and I can still remember how refreshing they used to taste in the heat. On the other side of our house, there was a large pond, where villagers cultivated shrimp and fish. Behind us was My Khe, where the sea and endless white sand seemed to stretch far into the distance.

During my earliest memories of childhood, when the bombing raids commenced, my family became used to hiding in the ditches. Others were not so lucky, killed by collapsing tunnels as they attempted to emulate us. Many residents made the decision to flee My Son. Some went to neighboring Ly Son, others were separated and their whereabouts became unknown. Many children became orphaned and adults lost their homes. Fields and gardens were totally destroyed. Since my parents were in a fortunate position to provide help to those who had suffered losses, a number of families came to them in desperate need of food and shelter. As everybody left in search of safer grounds, we headed to Binh Duc, which due to its relative peace, seemed like paradise.

With a population comprised mainly of fishermen and salt producers, Binh Duc seemed like a wonderful place. People here were very friendly and always smiled. Red and green colored boats appeared by the sea, ready for their day’s fishing. The shelling in Binh Duc was not as bad as the fighting in Son My. As the war started getting worse, our family lived with Mr and Mrs. Dong Hue for two years. My parents continued to operate their business in sewing and the wholesale market. I played with other children, waiting until the late afternoon for the sun to cool down, where we would catch crabs by the sea or play football with a plastic ball.

My Lai Massacre |

As the bullets rained and bombs fell constantly, the local market in Binh Duc came under heavy attack and we moved again, to Thuan Yen, where my younger sister, Thi Ha, was born. My family built a small house on the property of Mrs. Bo and my father worked in nearby Ting Hiep as a nurse in the district of Son Tinh C12.

Even as a child, I understood the threat and impact of war, a reality confirmed when my family was also forced to live apart from each other. It was hard for me to accept that my grandmother, who had lived all of her life in Son Hoi, lived alone. Her children all had their own families and had since moved. My parents took it upon themselves to take care of grandmother. I loved my grandmother very much, because she reminded me of my mother in both shape and character. My sister My Hong and I often delivered money for her to buy rice, something that excited me a lot, and I can still remember how warm her hugs were. The idea of running along with my sisters was always such fun, but it would not take long before I got too tired and asked for a piggy back ride.

There was so much to like about travelling on the B24 road through Thuan Yen, which were lined with bamboo trees with a backdrop of the mountains. The villages, surrounded by wheat fields and rice paddies, were often dotted with people toiling hard in the rice fields, planting themselves deep into the mud. This road led to My Lai, a place where everybody seemed busy working out how to best cope with bombings. The village of My Lai had become a recent target for gunfire, and the safest time to undertake all activities was either early in the morning, which is when farmers tended to their rice and vegetable plantations, and watered and spread fertilizer on their crops. The only other safe time was late at night, as this is when the fewest shots reigned over the village. Consequently, daily life was frantic. Every day, residents woke early to greet the sunrise, for this is when family meals were prepared.

Even in such a hostile environment, nobody would have predicted the events that took place on that day, March 16, 1968. American military units fired artillery shots across Thuan Yen, My Khe, and My Lai for one hour. They sounded like fireworks. Our village and neighboring hamlets were completely surrounded. At 11:00 am, helicopters started flying over My Lai, and some people in the neighborhood heard rockets being fired. My family and I learned that some residents had already been injured by the shots because the rockets were flying flow and landed in rice paddies where people were working in the fields. I could hear people scream and cry in a high-pitched wailing sound. Any civilians who were caught were marched into the center of the village. It resembled a makeshift prison yard full of men, women and children.

My father was not present in the household because he was away working in Ty Vinh Tinh Hiep, leaving my mother in charge of the household. Without any hesitation, she prepared an emergency kit for the children, fearing that we would also be taken from our hut. She hurriedly prepared a large brown canvas bag, placed some of my clothes in the bags and gave each of my siblings and myself 10,000 Vietnamese Dong, which we hid in our socks. I felt guilty about taking the money because it seemed like a fortune. We were then instructed to hide behind our house, which stored our home-made oils, medicines, textiles and fabrics. But before anybody had a chance to move, American troops stormed into our house and forced my mother, brothers and sisters to move onto the streets where everybody else was assembled. The last item my mother grabbed with her one free hand was her traditional straw hat, while desperately holding onto my baby sister, Thi Ha, with the other.

Once we were marched outside and told where to sit, my mother looked around and noticed the chaotic scenes where villagers were being pushed and shoved by soldiers. She noticed a nearby ditch near a neighboring house own by Mrs. Nhieu and told us all to move quickly, but to our dismay we found that it was already full. Crouching low, we eventually settled on a space near a tunnel opening. American troops were patrolling the area and continued to search tunnels. One old woman was struck on the lower back by a soldier’s rifle butt so hard, she fell to the ground in agonizing pain and could no longer walk. Horrified by what had just happened, I heard somebody say, “My God, we will all die.” This memory still haunts me today.

B&W version of photo showing Duc's mom's body by Ron |

One attribute I always remember about my mother was that no matter how hopeless the situation looked, she never accepted defeat. From our ditch, she spotted a nearby bamboo bush and hinted to us that we should head towards it immediately. The children went first and she following behind us. But no sooner had we begun to crawl through the crowd of people that a soldier saw my mother amidst the crowd, stormed into the ditch and grabbed my mother violently, ripping her clothes. I cried loudly in the hope that she would not be shot. Without warning, gun shots were fired into the ditch, hitting a number of bodies. As bullets, blood and flesh flew everywhere, my mother covered her body with her straw hat while hugging my little sister Ha close to her breast, and with her free hand, pushed me in the direction of a ditch adjacent to neighboring rice fields. She ordered me to protect my sister Ha and pretend to be dead so that the soldiers would leave us alone. We were not to move unless we knew the area was clear. For what seemed like hours, my little sister lay on her stomach and I sheltered her by doing the same.

As soon as the American troops moved out, my older sister and I searched for our mother and found her. She was seriously hurt, having been shot in the head and I knew nothing could be done to save her. However, she still had enough energy to give us one last instruction: “Hug your sister Ha, and take her to Grandma’s house. Don’t stay here any longer or they may come back and shoot you.”

A closer view of Duc shielding his 14-month old brother from |

These were the last words I heard my mother speak, and whenever I think about that day, it causes me great pain because I loved her very much. It saddens me to accept that among the numerous dead corpses littered the path between the village and my Grandma’s house, one of them was my own mother.

There is a famous panoramic picture of corpses amidst a green rice paddy taken by U.S. Army photographer Ronald Haeberle. But it does not include a shot of the dead women and children behind him. This is because of his position inside the helicopter where the photograph was taken.

When we were far away from the tower, a low-flying helicopter appeared, preparing for landing. I was very scared and hugged my sister. We lay down on the ground out to escape overhead bullets being fired in our direction. When I looked up, I saw helicopters quite clearly and there were a few American soldiers. One unarmed soldier was sitting outside the door, taking photos of the scene. If he had fired bullets, my sister and I would have been hit because the chopper was flying close to the ground. Only when the helicopter disappeared, I embraced my sister, Ha, and headed for Truong Son, in search for the road to Hoi An. We came across several dead bodies of local men on their way to work or the market.

From a distance we heard the sound of the American soldiers’ heavy gunfire. Houses were also being burned, and thick black smoke rose in the sky. I sensed that the helicopters were still patrolling the region. But all I could think about was why the inhabitants of My Son, especially innocent children, were attacked and killed. Many good friends and relatives of My Lai had their roots here, yet the village was now destroyed, and what was once a happy village was now gone. In grieving for the people who once lived here, I repeated “Why were they to blame? Why did you kill her?” over and over again.

Part II

Before my sister Ha and I reached our grandmother’s house, we arrived in Gia Hoa to greet my uncle, and asked for drinking water. He saw that we were covered in blood, from hiding in between bloodstained bodies in the ditch before our mother directed us to run away. He cried, a sign of being frightened for our well-being, and then immediately called over a village nurse, Mr. Hung. Our injuries were obvious; I was wounded in the forehead and my sister Ha in the abdomen.

It was in this time we discovered that my older sister, My, survived the slaughter by falling into a ditch and covering herself with dead bodies of people shot in rice fields. She too was covered in blood, but none of us knew the other was still alive. In fact, confusion reigned as to the fate of our mother. Although she was laying in the ditch when I last saw her, another village woman had told My that my mother had in fact escaped and began looking for her other children in the fields.

We listened to My’s story. She shared with us how she wandered the path of other adults taking a wounded child to the village of Truong for emergency treatment at a makeshift clinic. The baby was near death, having lost a lot of blood. Seeing a lost child in the village, a local family invited My to stay with them overnight. This is how Ha and I came into contact with our sole surviving older sister. I was excited to see her, but my first question was about the fate of my other two sisters, Thi Hong (11 years old) and Thi Hue (5 years old). My relayed the news I did not want to hear — they had been shot by American soldiers.

I tried to imagine how my father would react upon hearing all of this. His working commitments in Ty Vinh Tinh Hiep saved his life on that day, but with Quang Ngai province in South Vietnam, not the North, the South Vietnamese government had labelled him “a revolutionary”, meaning that he would be killed on the spot if caught by either American soldiers or members of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).

42nd anniversary of the Massacre at My Lai and Son My in Vietnam |

It turned out that he had been informed of the massacre the day after it occurred and hurriedly set about returning home, but was too late to see his wife and two of his children get buried by his own cadremen. He concentrated on gathering information concerning the day’s events which led to their deaths. A few days later, he braved the drizzly conditions to see his mother (my grandmother), buoyed by the slim prospect of seeing two of my sisters and myself. Our reunion was emotional, and every month he returned to visit us and check on our condition. He dedicated his life to ensuring that his surviving offspring could have a better life and a chance at receiving an education. The task would have been impossible if some of his closest friends did not act as our guardians in his absence.

My grandmother was poor — very poor. Her bamboo house with painted walls in a village on the River Son Hoi did not feel like a permanent home. I used to have fond memories of coming here with my sisters and swimming in the river, but something seemed peculiar now. Maybe my soul had died. Grandmother was old and frail, and she relied on buying and selling fish in the market in nearby Loc. It was her main source of income, but not enough for all of us to live upon. My sisters and I asked Mrs. Bon Thuong, a family friend, to stop working at the markets and assist with making food. Since we experienced regular food shortages, I grew rice and wheat. For what was left of our family, this was the new life — no school, no fun, just struggle.

Every morning, my sisters and I would rise early to commence working on the farm and came back late. There were days when we had no food. Our skin was black and broken from toiling in the sun, and we were thin. I wore a torn hat and rags for clothing. My meager possessions included a pick-axe and a discarded Korean-made bag, which I used to hunt and gather food and anything else deemed edible. My aunts and other locals scavenged for rice, wheat, corn and fluorescent tubes. Any payment came in the form of Oi, a Vietnamese fruit, and some corn.

When I worked in the fields, my little sister Ha accompanied me. She was undernourished and cried a lot, for she missed breast milk. My grandmother improvised by getting the neighborhood children to find somebody who could provide some breast milk in the village. We struggled to survive and were avoiding starvation, but once again tragedy struck our family.

On December 19, 1969, we were informed that lines of communication with our father had been cut off because the country needed him. All I knew at that stage was that he had “been sacrificed for our nation.” I did not know what to think or do. His financial and emotional support, no matter how infrequent, is what kept our household going. The one message I recall him telling me is to always listen to my grandmother’s teachings, for she educated us in times when we had no money to attend school.

Viet Cong soldier stands beneath a Viet Cong flag carrying his |

This changed in 1970, for I was accepted to attend my local school. What a bittersweet moment for me — my dream had been achieved, but at a cost. How I longed for my parents to see me attend class, even though our hunger pains became inexcruciable. The worst times occurred when we literally starved because there was no rice to be found. Eventually, we resorted to stealing wheat bulbs, a kind of sweet potato, from the garden of a local resident, Mrs. Ran.

Such tactics became more commonplace. My sisters worked harder to get more food because our grandmother was no longer able to travel to the market to buy and sell goods. My two sisters and I shared responsibilities for her wellbeing. My older sister My, who by 1972 was in third grade in the local high school in Long Tang, dropped out of classes, something she did reluctantly. Ha and I worked in the fields after school and would bring back some rice and sweet potatoes, but when Ha came home one night, we were shocked by her appearance. She was dirty, looked unhealthy, and often went without meals. By contrast to the amount of rice and other foods that Ha and I consumed, my older sister took very little.

At the end of 1972, Son Hoi continued to resemble a battlefield, and my entire family in Son Tinh Hoi An had to be evacuated. When the fighting had temporarily ceased a few weeks later, the signs seemed promising — maybe the war would finally stop. However, a bomb from a U.S. fighter plane destroyed my grandmother’s house, with a large crater hole evidence of its destruction. Thankfully we were all safe and accounted for, although it took us two months to erect another bamboo house that yet again seemed far from being a home. War instills a legacy of fear, that nothing is permanent.

My siblings, grandmother and I ventured towards the coast, looking for rice seeds in the fields along the way as part of returning to a stable routine. In Soi Hon, I saw my friends enjoy their childhood, laughing together as they flew kites and played football in the fields. This life is one I could have only dreamed of, but I resigned to letting them go, thus cutting off my communication with them. Survival was my first goal. If I acted in a carefree manner, then neither my family nor myself would have food to eat.

This war had deprived me of many things; half of my family, my childhood, and my innocence. Here I stood, a boy forcefully thrown into the life of an adult possessing only a discoloured hat and rags as clothes, a hoe in which to dig the earth and a Korean-made bag to carry whatever I owned. I had no money to buy even the smallest of items.

In the two years leading up to Vietnam’s reunification, I became obsessed with finding any long lost relatives that may have survived the war. My father’s fate was still unclear, but I guessed that having spent so long in the mountains, there must be a chance that he could still be alive, for soldiers were often away for long periods of time. I was excited when at the sight of seeing Hong, a long-time friend and son of a local man Mr. Ho. But this feeling of ecstasy was cut short when I received a visit from my father’s friend, Mr. Phan The Manh, who held a high rank in the resistance unit.

“Your father was a very brave man and sacrificed himself heroically,” he said, and immediately consoled me. These few words confirmed my worst fears. My father was shot and killed by American soldiers when his ambulance team attempted to help a wounded fighter. It was a crushing blow for me; I remembered his message about the importance of learning and making the most of every opportunity.

When I learned that I would be elevated from the sixth grade at Son Hoi school to attend a higher level in nearby Son Hoi Thanh, the pride and joy that I felt was immense. But the teacher turned me away from class on the first day because I did not wear long pants. If only she knew just how difficult life had been for me up until this point, then maybe her heart would have been kinder. When I went home and relayed the news, it must have seemed like just another setback. But this one seemed more significant. My aunt gave me a pair of black khaki pants once owned by her late husband, and for the first time I now possessed my first pair of long pants and could attend school. After three lessons, the teacher who refused to let me into class was reduced to tears when I told her what had become of my family. What more could one do?

Part III

History books will tell you that on April 30, 1975, the tanks rolled into Saigon, signalling the end of Vietnam’s war and that my fellow people could start to rebuild their lives. But the difficulties of years gone by were not automatically erased from my memory, like the time when I was nearly beaten to death while collecting crops.

My Son temple, Dui Phu village, Vietnam Courtesy: Bernard Gagnon - Wikimedia Commons |

Some of my family began moving back to our former village of Son My, ending my two year absence. This meant that I commenced attending a local school. Compared to my classmates, I was relatively large, but this did not stop my obsession with hunting for extra food to supplement our diet. One afternoon, two of my friends, Dinh and Lien, joined me in trekking into the mountains in hope of harvesting potato tubes, but our afternoon’s toiling yielded no potatoes or Oi [a Vietnamese fruit]. As the sun set in the distance, we walked down the mountain and to our good fortune, stumbled upon a dense clump of tubers, which were very good. All three of us cleared the grass to create a path and in front of us were plenty of onion bulbs to collect. Within a short time, we collected half a bag full. But up ahead we spotted a young man armed with a stick that he used to collect bags and we immediately we sensed danger.

Our first instincts were to lay low in the long grass in the hope that we would not be discovered, but I was caught and without having any chance to think about what punishment awaited me, I found a hoe being pointed in my face. The man pulled me out of the grass roughly and used the hoe to beat me in the stomach, and across my shoulder and back. I cannot remember how long the beating lasted because I had passed out, but it ceased only when my body stopped twitching. All the food my friends and I had gathered was handed back to the man who inflicted the beating. My whole body was swollen and I was unable to attend school or work in the field. When my sister Mỹ and my grandmother asked what had happened, I told only half of the story. The man who inflicted the thrashing, it turned out, lived behind the house of our family friend, Mrs. Bon Thuong. My sister recognised him and other young people he associated with quite often. To this day, I believe that he feels guilty about the incident. Maybe it is because he instigated the attack and now realizes that I have no desire to seek revenge.

Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, Jr., only 24 at the time, landed his US Army between soldiers and several |

My pain and anger is not aimed at only those who took the lives of my family members, but at those who have covered up mistakes years after and have refused to say anything to me. Many reporters from around the world have come to My Son. They have worked with the Quang Ngai municipal staff in their offices and talked several times about the deceased. But I believe the media has been misled by authorities on certain matters. A number of survivors and their relatives have never been asked about their wishes. These include Mrs. Pham Thi Tro, daughter of Mrs. Nhieu, Le Thi Em, Pham Thi Hien, Bui Thi Ha, and Bui Sanh, the grandson of Mr. Huong Tho. They still live less than 800 yards from the memorial house, each one in dire poverty.

You only need look at photographs of the victims taken by U.S. Army officer Mr. Ronald Haeberle. These include:

Mrs. Nguyen Thi Tau, photographed with her closed mouth covered by a straw hat, may have lost her children but this certain that many soldiers have shot her children. Two of them were saved.

Mr. Nhieu’s wife and daughter escaped through the back door of their hut and hid in the rice field. They were lucky to flee, for five members of their family were killed. They also witnessed many gruesome images and experiences in their home.

Mrs. Pham Thi Thuan lost five people in her family, all killed by gunshots. I estimate that about 20 people who ran from the corner of her house sought shelter in the ditch, or other lay down in the garden. Others were hiding behind the altar where the family burned incense and gave offerings to their ancestors. They were all pulled out and shot by U.S. soldiers.

Mrs Thi Tuyet Do lives in Pleiku. She and her family were pulled out by U.S. soldiers and ordered to sit in front of the house before being instructed to enter the ditch. Of the 170 people, most in the line of fire were women and children. Many of them were killed, but you survived if you were covered by the other bodies.

Mr. Dat Pham testified that his wife was shot and injured, while a seven month-old child crawled out of a burning house and wandered towards the ditch; the child was shot by U.S. soldiers, covered in dry leaves, and burned.

Ms. Truong Thi Le lived because she lay quiet underneath two dead bodies and pretended to be dead.

Ha Thi Qui is now 83 years old and was wounded in the hip and lay there quietly, also underneath corpses. She later attempted to crawl home. On the way, she saw many injured persons and bodies of women, some of whom had been raped by U.S. soldiers and then shot.

I saw Pham Thi Trinh, then 11 years old try to crawl out of the ditch to the top, just like Mrs. Pham Thi Muoi, whom was only 14 years old when she was found next to a house, raped and shot dead by a U.S. soldier.

A mother and 7 month old child were covered in dry leaves and set alight by U.S. soldiers.

The house of Mr Le contained 15 hidden people who were found and thrown in the trenches. Nobody was spared.

Ms. Trinh’s eight year-old daughter was shot by U.S. soldiers when attempting to escape a ditch while carrying a mouthful of rice.

Mr Tấn Huyen Tran, from Khe Thuan village, said that his grandparents, his parents, and child were shot dead by U.S. soldiers.

Many people from the international press have come with their camera crews to film stories about My Lai in the past. Authorities paid members of the press to stay about 800 yards away from areas where the poorest survivors and their families lived, to discourage any contact and prevent details being released. Film director Oliver Stone worked in Pinkville with an interpreter, dealing with the press to obtain details for making his film. But our testimony and history has been ignored. My family received no help from the community or the state. After Vietnam became a united country, I learned that my mother’s tombstone had been issued with the wrong date of birth and even worse, the incorrect picture. When I raised this with house memorial officials, they did not take up my complaints further. Perhaps my stories of a handful of cold rice and going numerous days without food in my childhood interfered with their seemingly lavish lifestyle.

For any of the 130 American soldiers involved in the massacre, people such as Ernest Medina, William Calley, Oran K. Henderson, Samuel W. Koster, Eugene Kotouče, have you considered what impact your actions had on the children who lost their parents? Some of these children are now adults and they still live with the nightmares of being dragged out of their huts, being thrown into ditches, and watching machine guns and grenades slaughter their family members. After 42 years, you still have not come back to seek redemption. What did the innocent people of Son My and the surrounding hamlets do wrong to deserve being killed? How many screaming children can you recall crawling or lying on the ground in a puddle of blood? When you opened fire, mothers were breastfeeding children. Elderly village women and defenceless and unarmed men died with frightened looks in their eyes.

Hugh Thompson |

People that we respected and paid reverence to, you spat in their faces. You raped teenage girls and young women. Before committing your evil deeds, your units slowly encircled us, preventing any chance of escape.

Ronald Haeberle |

Maybe you do not care, in which case, an apology is useless.

However, there were some soldiers who showed compassion and I would publicly like to thank them. These people include Mr. Ronald Haeberle, who took a photo of my mother and other images from his helicopter.

These include the two pictures of the four young children he photographed before they were shot by U.S. soldiers, and another of two children lying on the street. The people of Son My remember him very fondly for his actions to prevent further loss of life.

I also pay my respects to Hugh Thompson, who landed his helicopter to rescue an eight-year old child and take her to a hospital after receiving a radio call from Glenn Andreotta.

Larry Colburn, Ron Ridenhour, Seymour Hersh (the investigative journalist who exposed the My Lai Massacre to the world in 1969) and William R. Peers all tried to tell the world exactly what took place, but were silenced by the U.S. government.

Ron Ridenhour |

Although I now reside in Germany, I am speaking up on behalf of the residents who continue to live in My Lai and remain committed to seeing justice prevail for the deceased and survivors.

Epilogue

Tran Van Duc has told Foreign Policy Journal that in his recent visit to My Lai in July and August, he contacted senior officials in Quang Ngai Province. These include the Police Director of Quang Ngai Province, Mr. Le Xuan Hoa, Province Chairman, Mr. Nguyen Xuan Hue, and the Director of Sports Culture and Tourism, Nguyen Dang Vu. According to Mr. Tran, Mr. Nguyen Dang Vu has “promised to repair the reporting of false information about my family.”

On August 13, 2010, Tran Van Duc emailed Foreign Policy Journal, stating that in a meeting four days earlier, the Quang Ngai Provincial Department of Culture, Sport and Tourism expressed their condolences for the suffering endured by the Tran family as a result of the My Lai Massacre, and would work to change any incorrect the details regarding the identification of Tran Van Duc’s mother.

Foreign Policy Journal has also learned courtesy of an email dated August 30 that Mr. Tran wrote to Vietnam veteran Mike Boehm dated August 30. In the email, Mr. Tran says that he has removed an inscription as part of “An American Peace”, denoting the remains of his mother and two sisters killed on the day of the massacre, along with 72 other civilians.

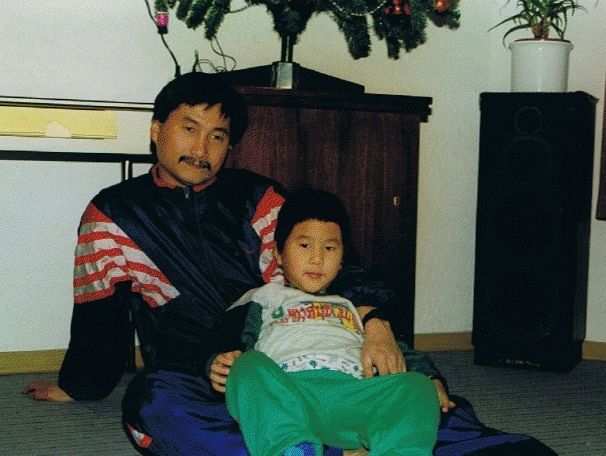

Tran Van Duc and his son |

Mr. Boehm, who has spearheaded a number of community initiaives in Vietnam through the Madison Quakers Inc., told Foreign Policy Journal that he assumed Mr. Tran “is referring to our of our humanitarian projects when he is writing about ‘An American Peace’”. He said that Madison Quakers Inc. has funded a number of projects in My Lai and Quang Ngai Province, including the construction of four primary schools, the establishment of the My Lai Loan Fund for women to start small businesses and the My Lai Peace Park.

Mr. Boehm said that he “heard of, but not visited” any plaques commemorating the tragedy in My Lai.

“For more than 42 years media writing or filming about My Lai concentrate on the massacre. My organization is focused on helping those still living,” Mr. Boehm said.

Comment was being sought from the Quang Ngai Provincial Department of Culture, Sport and Tourism.

For verification of the ages of the fallen victims of Mr. Tran’s family, a formal request for an official list of the victims in the My Lai Massacre was sent to the Embassy of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in Canberra, Australia, on September 2, 2010. For the purpose of this document, a list of the names of the 504 people killed has been obtained from the following source: http://www.countryjoe.com/

The webpage attributes the document as being supplied by the Vietnamese Embassy in Washington DC, based on a request by Trent Angers, author of The Forgotten Hero of My Lai: The Hugh Thompson Story. According to the publication, the names and ages of the deceased are listed as follows:

Nguyen Thi Tau, (mother), 32 years old

Tran Thi Hong, (sister), 11 years old

Tran Thi Hue, (sister), 5 years old.

Mar-16-2008: My Lai Massacre in Vietnam Happened 40 Years Ago this Weekend - Tim King Salem-News.com

Mar-17-2010: The 42nd Anniversary of the Massacre at My Lai - Chuck Palazzo Salem-News.com

Sept-07-2010: The Diaries of My Lai Orphan Tran Van Ducby David Calleja

The 504 People Killed in the My Lai Massacre - Country Joe's Place

The 504 People Killed in the My Lai Massacre

The names of the deceased are followed by their age and sex. A brief tally shows that 50 of the people were three years old or younger, 69 were between the ages of four and seven, 91 were between eight and twelve, and 27 were in their seventies or eighties. The list was provided by the Embassy of Vietnam in Washington, D.C., in response to a request by Trent Angers, author of The Forgotten Hero of My Lai: The Hugh Thompson Story.    |

|

Articles for November 21, 2010 | Articles for November 22, 2010 | Articles for November 23, 2010

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Harry June 1, 2018 4:22 pm (Pacific time)

For decades, I've been haunted by that photo of the young Vietnamese woman biting on her "nong la." I am so sorry that this horrible massacre had occurred. My deepest sympathy to the survivors.

Lynn R. Smith June 24, 2012 2:41 pm (Pacific time)

Thank you Editor. This story needs never to be forgotten. I wrote to Mr. Duc Van Tran and he responded. I just now welcomed him to attend our very first reunion with my unit, the 52d Military Intelligence Detachment, 11th Infantry Brigade, Americal Division in Cocoa Beach, Fl next February 2013. Most of us knew these criminals on a personal level. And we do not condone what they did and Mr. Duc Van Tran's story needs to continue. You Sir and Tim King would also be welcomed to join us should you choose to. Best Regards, Mr. Lynn R. Smith

Tim King: Dear Lynn, thank you so much, I have your email and I would be very happy to attend if possible, you are the 99% and I would be proud to meet all of you and learn more, thank you and particularly for inviting our friend Mr. Duc Van Tran, it would be great if these elements could come together, thank you!

Lynn R. Smith June 23, 2012 9:37 am (Pacific time)

I have nothing but contempt for Calley, Medina, Henderson and Koster and all of those who committed this mass murder and rape and those who covered it up. Calley is a coward. Likewise, so is Medina, Henderson, and Koster. I should have finished taking care of Calley and Medina at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. Henderson was the dumbest CO we had in Vietnam. I didn't like him or Koster. I could tell you a lot about these individuals because I dealt with these criminals personally. They all should have faced being shot by a firing squad or put in jail at hard labor for life.

Editor: All respect to you Lynn

bergevin March 20, 2012 9:34 pm (Pacific time)

damme not a human coldbood killer,worst than hitler,all the whoever invole dead penalty or life in prison ,no excuse what so ever ,just an animals killers period..................

LanceThruster December 6, 2010 9:34 am (Pacific time)

The horror and sadness of Mr. Duc Tran Van's recounting of the massacre of beloved family members and neighbors while so very young is heart-wrenching. He too was one of the heroes of that day as his actions prevented his brother and himself from becoming fallen victims of the slaughter. His survival allowed him to be there for his remaining family and share his story with others in a most poignant and graphic way. Armed conflict always involves senseless death and destruction, but what he experienced at the hands of those who believed their own sacrifices were for the good of his people was beyond the pale. I became draft age in ’75 as America’s direct military involvement in the conflict had essentially ceased. I had considered enlisting but did not feel I could trust my government with regards to those it might determine warranted killing. I was reminded of this when my friend’s son Adam, part of Marines 1/5 for the fall of Baghdad in the second Gulf War, returned home from Iraq. When I cautiously asked him about his experiences in a combat zone, the first words out of his mouth were, “We killed people for no reason.” I learned from him that even with very specific rules of engagement, innocent people would die. A vehicle would approach his checkpoint too fast, too erratic, and not heed signals to stop or slow down, and he and his fellow Marines would fire upon the vehicle and its occupants. He told me about the time he did just that, and when he went to inspect the vehicle, it was full of dead and wounded women and children, some of whom were screaming or crying or moaning, in terror or pain or anguish. He bears no physical scars from his tour of duty, but is on PTSD status. I was traumatized by merely hearing of some of his encounters over there. I can only imagine the toll it takes actually living them. To Mr. Duc Tran Van; I am truly so very sorry you and your family and your country suffered so as a brutal war was waged across your land. I have tried to remain informed and active politically so that I could do whatever I can to help prevent my country from inflicting further such tragedies on others. As you might imagine, sometimes I too feel very helpless in this regard. You and Tim King have done much to remind me that sometimes courage can be as simple a thing as to just keep moving forward. And for that, you have my sincere gratitude.

John November 22, 2010 2:16 pm (Pacific time)

The official death toll (On March 16, 1968, during the latter part of the NVA/Viet Cong criminal TET Communist Invasion), according to the US government, was 347. The Communist Vietnamese government, in contrast, asserts that 504 villagers were massacred. The Communists also never refer to the hundreds of thousands of civilians that they butchered, nor the brutal re-education camps, nor address the reasons that millions of Vietnamese risked life and limb to escape the brutal regime that is still in power. This was a horrible act, and is a chilling reminder of what can happen when soldiers cease to regard their opponents as human. The soldiers in this crime, at the latest, entered the military in 1967, long before draft-level qualifications were lowered to "net" some of the lower classes of people we find mostly in our inner cities. The writer wrote: "Many, if not most of the men in 'Charlie Company' under the command of Lt. William Calley, have died since the end of the war, many by committing suicide." And: "large number of the My Lai soldiers were 'Category 4' ASVAB entrants. They would normally have been denied entry over extremely low intelligence, mental problems, criminal pasts and other issues. Congress lowered the bar, and then came My Lai. President George W. Bush did the same thing during the peak of the war on Iraq." It would be interesting to see your sources, which do not exist and demonstrates that facts for some reason in this matter must be made up. Why? In addition, all those Americans who reside or work in Vietnam dare not question the criminal past nor the ongoing totalitarian tactics of the government there unless they are prepared for a very intense blowback. When and if a time comes when the citizens can openly challenge that government without fear, then you have something. The same thing applies to governments in China, Cuba, Venezueala, etc. , and literally all Islamic countries. I feel horrible about this My Lai crime, but it pales compared to what the communists did to Americans and their own citizens. Maybe a balanced account would be a story worth doing, especially for those who have no historical understanding of this part of the world, but it's doubtful it will happen at this site for very obvious reasons.

Tim King: I will go back to my sources and check the dates, this is something I learned long ago when studying the atrocity that happened at Son Thang. At any rate, I agree that the Communist forces committed terrible acts against US serviceman, but I don't see how that nullifies or justifies this act. I'm sure that is not your objective. By the way, the same things that you accuse these nations of is taking place here also. And as for my lack of experience in SE Asia, that may change very soon. My goal is not to defend the acts of a political philosohpy; this story is about mass murder.

[Return to Top]©2025 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.