Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Jun-18-2012 18:53

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

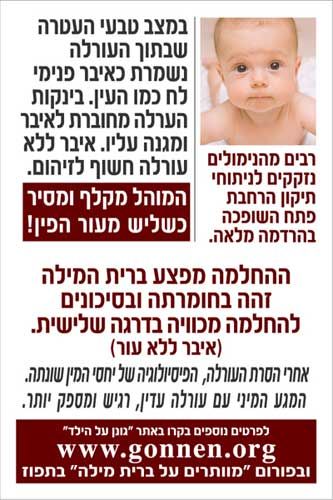

Even in Israel, More and More Parents Choose Not to Circumcise their Sons

Netta Ahituv Special to Salem-News.comBecause no systematic record is kept of the number of circumcisions performed in the country (see below) there are no exact data.

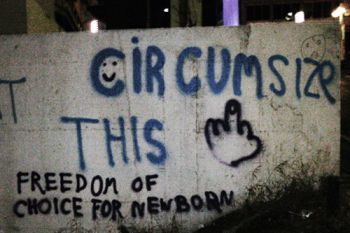

Street art at Rehov Frishman, Tel Aviv. |

(TEL AVIV Ha'aretz) - When their first child, a son, was born 11 years ago, it was clear to Eran Sadeh, now 42, and his partner, Maya, 40, that he would be circumcised.

“We arranged it with a mohel [ritual circumciser] and then I started to look for information and references about the man on the Internet,” says Eran, a former lawyer-turned-computer instructor in a software company. But while surfing the Web, he came across a world of information about circumcision. “For the first time in my life I learned what’s cut, how it’s cut and what the risks are. I didn’t have a clue until then. The word was just another check mark on the list of tasks related to the birth. I treated it almost as a bureaucratic process. But the new information I came across shook me, and I knew I wasn’t capable of inflicting that on my son.”

Eran Sadeh is not alone. In the past decade, increasing numbers of Jewish parents in Israel have decided not to have their sons circumcised. They hardly constitute a majority, but today, in contrast to the past, many Israelis are considering this idea.

Because no systematic record is kept of the number of circumcisions performed in the country (see below) there are no exact data. Indeed, the Health Ministry itself has no figures regarding this at all. However, according to most estimates, between 1 to 2 percent of Jewish males born in Israel in the past decade were not circumcised. Furthermore, there is no obligation for parents to formally report whether their sons have been circumcised or not, either at the rabbinate or the government authorities.

An informal online survey conducted in 2006 by the Israeli parenting portal Mamy found that of 1,418 parents of boys, 4.8 percent did not have them circumcised. The reasons given: 1.6 percent were not Jews; 2 percent objected to disfiguring the body; and 1.2 percent refrained because the act is painful.

The survey also found that nearly a third of the parents would prefer to forgo circumcision but nevertheless have it done for social reasons (16.6 percent), health reasons (10.4 percent) and because it is important for the grandparents (2.1 percent).

“I realized that the phenomenon is widespread and includes people of various backgrounds when friends of mine − a couple who are lawyers and conformists, not rebellious in any way and certainly not haters of Judaism − decided not to circumcise their son,” says Riki (not her real name). A 34-year-old mother from Petah Tikva, she too did not have her son (who is now three) circumcised after hearing about this option from friends.

The changing attitude of Israelis toward the axiomatic character of circumcision is evident during meetings for the Kahal organization. Kahal offers support to parents who are undecided about whether to have their sons circumcised, and to those who decide against circumcision. Twelve years ago, when the organization was founded, meetings were held every three months and involved about 40 families. Presently they are held every two months, and there are about 20 parents at each meeting, most of whom are agonizing over circumcision.

One of the founders of Kahal is Ronit Tamir, 46, a software engineer from Tel Aviv who is the mother of three children: two daughters aged 16 and 10, and an uncircumcised son, aged 12. Tamir says that Kahal was originally founded as a support group for families with uncircumcised children. “But after a year we found that those who were most interested were the still-undecided parents, not the veteran parents. In fact, we learned that uncircumcised boys have no problems at all, certainly not social ones, so their parents are not in need of support.”

Her experience with parents over the years shows that after the stage of soul-searching before the first child, “they no longer remember what all the fuss was about. The subject is usually forgotten when the baby is about half a year old.” Tamir adds that, contrary to expectations, not all the parents involved are “Tel Avivians, bohemians, hippies or weirdos.” In fact, according to her information, most are not from Tel Aviv at all but from Rishon Letzion.

Despite the fact that the non-circumcision choice is becoming more widespread, the reactions it draws are still negative. To begin with, since the discussion is about the male sex organ, it is very complex and highly emotional. Second, it is the only precept in Judaism which is irreversible when undertaken, and therefore it is natural that it provokes a desire to justify it firmly − or, by the same token, to justify avoiding it with the same firmness. (Some maintain that not being circumcised is effectively also irreversible, because having the act performed at a later age is more traumatic than in infancy.)

The social argument

In addition, a decision not to circumcise is frequently considered a provocation against or subversion of one’s social group. It embodies the great tension between the aspiration to ask and to question what is taken for granted, and the natural tendency toward social conformism and the need to be accepted. That tension sometimes erupts in the form of verbal fireworks.

For example, one mother who did not have her son circumcised relates that she recently contacted a pediatrician about a rash on the boy’s face. The doctor had the boy disrobe so she could see if the rash had spread.

“When she saw that he was not circumcised,” the mother recalls, “she was shocked and told me it was unhealthy. In the discussion that developed between us she understood that the health-related argument was not working, so she switched to the social argument: ‘He will be different’; ‘Others will make fun of him’; and, of course, the old standby: ‘You are doing your child a great wrong.’”

In fact, Dr. Avshalom Zoossmann-Diskin, one of the most vociferous objectors in Israel to circumcision and the founder of Ben Shalem – an organization which fights circumcision – says that in his many years of anti-circumcision activism he has encountered only one harsh response. That was in 1999, in connection with a petition he submitted to the High Court of Justice against circumcision on the grounds that it violates the Basic Law on Human Dignity and Freedom, the Children’s Charter of Rights and criminal law. After the petition was rejected, the interior minister at the time, Eliahu Suissa (Shas) stated that “the petitioner should be thrown out the window.”

The powerful emotions the subject generates is also the reason that some of the interviewees for this article did not want their name published. They wanted to contribute their opinion and personal story − but without making their children the focal point of the struggle against circumcision.

Another group of interviewees agreed to be identified only by their first name, to protect their children’s privacy and leave them the option of talking about the subject when they are older, if they wish. Finally, there were some who agreed to have their full name published, believing that they have no reason to be ashamed of their choice and also being ready to deal with the responses.

Among those in the latter group are Eran and Maya Sadeh, who live in the north of the country. They say that the most shocking piece of information they came across about circumcision, and the one that influenced them most deeply was the view of Maimonides on the subject (see Circumcision in Judaism below). The great 13th century physician and philosopher “accorded emasculating justification to circumcision,” Eran Sadeh says. “He maintained explicitly that it is done in order to affect male sexuality and reduce the pleasure of the sex act. For me, that connected with female circumcision and shocked me. I immediately read up on the physiological aspects and understood that what Maimonides said is correct: Circumcision affects the functioning of the genital organ in sexual relations.

“I connected that with my legal knowledge about human rights and understood that it’s wrong from that point of view as well. You take a person in the most vulnerable and helpless condition and amputate part of his body. Maimonides talks about that, too. Circumcision is performed when the infant is eight days old, because the bond between the parent and the child is not yet very strong and the parent is capable of inflicting this on his son. It is a gross violation of human rights, perpetrated by none other than the child’s parents, those who are responsible for protecting him.”

Maya Sadeh has a son from a previous marriage who underwent circumcision and needed corrective surgery afterward. The complications prompted her to accede easily to her husband’s wish not to have their child circumcised. According to Health Ministry data, in 2010 there were 57 cases of complications following circumcisions performed by a mohel, and a further 19 where the circumcision was performed by a doctor. There were 44,665 Jewish boys born in Israel that year, indicating that the proportion of complications is less than 1 percent. (According to the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, the committee that oversees the mohelim dealt with 54 cases of complications in 2011.)

“The most frequent complication is bleeding in the first hours after the circumcision. That happens if a blood vessel does not close well,” explains Dr. Daniel Shinhar, a pediatric surgeon. The Rabbinate states that in 2011 there were 48 cases of bleeding.

“The second most frequent complication is infection [5 cases in 2011],” Dr. Shinhar continues. “Following that is potential damage to the organ itself, resulting in amputation of part of the organ [1 case in 2011]. A further complication, which occurs as a result of the circumcision itself and appears later, is the narrowing of the opening of the urethra, thereby causing urination problems.

“Another complication can cause an unsightly cosmetic problem in the form of surplus foreskin. That happens in about 5 percent of circumcisions, but only one in 10 of them will need corrective surgery. It is important to point out that in this case, the surgery is for cosmetic reasons and is unrelated to medical or religious considerations.”

‘Collective self-persuasion’

While parents who have their children circumcised are concerned about possible physical consequences, those who do not are apprehensive about possible psychological side effects. What most concerns those who attend Kahal meetings, for example, is the social implications of the child being “different.”

“People always ask how many uncircumcised boys there are in Israel, but I don’t have an answer to that,” Kahal’s Tamir says.

Frequently there are also objections by the extended family relating to issues of Jewish identity. Parents who decide against circumcision for their children are usually concerned that they will be boycotted by the family. However, Tamir’s experience is that the anger of most grandparents diminishes at the sight of the grandchild and eventually disappears altogether.

'Ido', an uncircumcised Jerusalem resident, had a similar experience. His paternal grandmother did not stop crying from the moment she heard that her grandson was not going to be circumcised − until the first time she saw him and was enchanted by him. After that, he says, the subject never came up again.

The Kahal meetings often reveal disagreements between husband and wife. According to Tamir, it’s a 50-50 split: In half the cases it’s the male partner who doesn’t want his son circumcised, the other half, the female partner. Moran, 31, and her husband, Nir, 34 (not their real names), from Tel Aviv, are one such couple. Their son is now a year old.

“At first we both agreed not to circumcise,” Moran says. “But then friends of Nir said that would be a mistake, and he started to have doubts. I also had doubts and I decided to do some research. Suddenly I realized that people do more research about strollers than they do about the issue of slicing off part of their son’s body. After viewing a documentary film showing exactly what happens in circumcision, I knew I wasn’t capable of doing that to my son. I had to stand firm and defend my decision. I understood that it wasn’t a proper or acceptable action, and certainly not a logical one.”

The first months, Moran says, took a toll on her relationship with her husband, but they got through it. Things are now peaceful at home.

Another topic that comes up in meetings is whether the foreskin of the uncircumcised requires any special treatment. Tamir explains that nothing need be done, just to let it be. “It is not necessary to clean under the foreskin, pull it back or insert anything into the penis to remove dirt, because there is no dirt. You just treat the organ like you do a finger.

“I also inform parents that some doctors are inclined to ‘blame’ the foreskin for all kinds of diseases − even if the infant has an ear infection. We have doctors in Kahal who check on a volunteer basis whether the foreskin is ‘guilty’ of some disease. Finally, I point out that this is a regular, healthy organ and the likelihood that it will cause problems is negligible.”

To avoid possible problems, most parents of uncircumcised children inform the preschool teachers of the situation in advance. “None of the places to which I sent the children made any fuss over it,” one mother notes.

Some of the parents who decided against circumcision did so after reading an article or viewing a film on the subject of female circumcision, and realizing the similarities. Ido’s mother, for example, relates that five years before he was born, she read an article in Britain about female circumcision and saw that the arguments made by advocates of circumcision for females were the same as those voiced by her secular Jewish friends in favor of the procedure for males. As a result, she and her husband decided not to have Ido circumcised, a choice that in 1980 was very unusual and was vigorously opposed even by completely secular Jews. Here, too, tempers flare quickly.

“When female circumcision is mentioned, everyone joins the protest and the debate ends,” Moran says. “People ask me, ‘How can you compare? We are not hurting our children.’ Well, the Africans and the Muslims who perform female circumcision treat it in exactly the same way that we treat male circumcision. They say it’s healthier, more beautiful and makes women prudish. The anger arises from broad, collective self-persuasion.”

The Internet has also played a part in increasing the anti-circumcision movement. For example, for the past 11 years the Tapuz portal has hosted a forum called “Forgoing circumcision” (in Hebrew).

Galit (Haaretz is in possession of her surname) is one of the forum’s three managers. She lives in Tel Aviv and is the mother of three children, two of them boys, aged 11 and 6 − both uncircumcised.

“Since the advent of the forum there has been a constant increase in the number of people entering it,” she says. “My feeling is that there are a lot more undecided people today. In other Tapuz parenthood forums, too, it is legitimate these days to discuss the possibility of forgoing circumcision. The feeling is that even people who have their children circumcised are more receptive concerning the other option.”

According to Ronit Tamir, the question of whether an uncircumcised boy is Jewish often comes up in Kahal meetings. “It’s usually in the wake of claims by the extended family that the boy is not a Jew. That of course is not the case: If the mother is Jewish, so are her children.” The Rabbinate confirm this statement.

The Sadehs describe themselves as secular people with a deep bond to the country. “We feel that we are part of the community in which we live. Our son speaks Hebrew, is familiar with Hebrew literature and knows all the Jewish festivals. There is no way that children who grow up in Israel and attend the school system miss out on the country’s Jewish and Zionist character and on the ethos of Jewish life here.”

Galit, from the parenting forum, says her decision not to have her children circumcised actually helped her crystallize her Jewish identity. “I did not arrive at that decision from an anti-religious posture: I am against the act itself. After the decision was made I started to think more deeply about what Jewishness means to me. I discovered to my happiness that the ability to stand fully behind my traditional choices, in terms of my relations with Judaism, had deepened.”

'Ido' recalls that when the rabbi came to teach him the weekly Torah portion ahead of his bar mitzvah, “he explained to me about who a Jew is. One of the things he mentioned was that a Jew is someone who has undergone circumcision. I was 12 and a half at the time, and I remember smiling to myself and thinking that he didn’t have a clue. Already then I understood that being a Jew goes far deeper than what the rabbi thought regarding me − that a slice of the body is not a guarantee that I will feel true identity with Jewish culture.

“Rabbis can say whatever they want,” he continues. “I know that my Judaism cannot be taken from me, because I am part of a particular cultural history. I am a Jew who believes in precepts such as ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’; ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’; and ‘Remember the stranger, because you too were a stranger in Egypt.’”

Fear of being different

Writer Meir Shalev noted in his column in Yedioth Ahronoth, in 2005, “It is not only circumcision itself that should make us wonder, but also the enthusiasm we display in preserving the custom. Something very strange is going on here. Why is it that secular, free Jews − and I count myself among them − who ignore the precepts relating to sexual intercourse, eat nonkosher food with a strong hand and an outstretched jaw, and abstain even from wonderful and important precepts such as observing the Sabbath, insist in observing precisely this brutal, cruel and primitive commandment of all the commandments? This seems to go beyond sheer consensus or considerations of health, but the secret itself eludes me. It’s a riddle to me and a riddle it will remain.”

This fear was given expression in the first season of the Channel 2 series “Tironut” (Basic Training), broadcast in 1999. One of the plot threads is about a soldier of Russian origin who is ashamed to shower with his buddies. Finally the sergeant forces him to do so and his secret is revealed: he is not circumcised. Later in the series, the soldier gets special leave so that he can undergo surgery to remove the foreskin.

“Of all the arguments, the one about [feeling different in] the army is the only one that makes me angry − as though we were living in Sparta and everyone here is raising soldiers,” says Ido, who has gone through three decades of being uncircumcised: in preschool, school, the Scouts and a combat unit in the army.

Asked whether he was mocked or otherwise singled out in the army or in other social frameworks, he says, “The short answer is: No, no one made fun of me. The long answer is that I never made a big deal out of it. I didn’t walk around naked, provocatively, but I also did not hide anything, act ashamed or ask to shower after everyone else so they wouldn’t see.

“My mother says, and I agree with her, that she gave me the choice whether to be like everyone else or not. When you have a child circumcised it’s a one-way ticket, but when you don’t, it’s a two-way ticket with which you can return if you want. I have never wanted to return. I am glad I was not circumcised. I feel wholly in harmony with myself.”

The question of choice is also addressed by Ayelet and Aharon (not their real names), parents in their thirties from Ramat Gan. Their son, who is now five months old, was not circumcised.

“My main feeling was that I was giving my son the option to decide for himself,” Ayelet says. “It is his body and I didn’t want to do anything to his body that he would not be able to restore.”

Ayelet, who works with children, has come across other uncircumcised children and has seen that neither they nor their playmates make a fuss about it. “I was present when they showed themselves to one another, as children do, and didn’t see anyone being treated differently. An unpopular child will be unpopular irrespective of whether he is circumcised. He will be made fun of because he wears glasses, is fat, has weird parents and so on. But a popular child will be popular with or without a foreskin.”

Tamir adds that when parents tell her they want to have their son circumcised in order to remove one reason that others will make fun of him, she replies that this is just one reason out of a hundred that is liable to provoke the kind of cruelty that arises among children.

For her part, Moran believes that the social concern is that of the parents, not the children. “They are afraid for themselves, because they were the ones who made the decision and they are the ones who will have to explain it, and that is not easy for everyone.”

“It took months for me to get over the fear that I was making my child an anomaly,” Eran Sadeh says. “I asked myself what will happen to him in kindergarten, in school, in the army and with girls. I went to a few meetings of parents who have uncircumcised children and that reassured me. I met many parents who told their story and I saw that they were normative people, not eccentrics. I realized that it wasn’t all that bad and that it would be all right.

“After a few meetings I felt I had no more qualms about the decision. For the first time in my life I had to forgo my anonymity and take an active position about something and fight for it.” That need prompted Eran to create a website, “Gonen al hayeled” (Protecting the Child; in Hebrew), an online information center about circumcision.

Says Galit, from the parenting forum: “Over the years, we become happier and more accepting of the decision. We understand that the fears we had are not materializing and that the children are happy and socially popular.

“Our children are pleased that they were not circumcised. They never got angry at us, as the advocates of circumcision threatened would happen. People think that it is only a matter of time before a child who does not undergo circumcision asks to have it done. That is simply not so. Our attitude toward the subject at home is businesslike and simple, and we do not overlay it with ideologies, protests and unnecessary feelings. We also do not focus on other parents who had their children circumcised and we do not make comparisons with other children. We view that decision as one of many parenting decisions we make in our children’s lives.”

On the other side, surprisingly, is Dr. Hanoch Ben-Yami. A pioneer of the Israeli anti-circumcision movement, Ben-Yami teaches philosophy at the Central European University. Only a few months after attacking circumcision in a Haaretz article in 1999, he had his son circumcised. The boy is now 13.

“The main reason we did it, and what finally tipped the scales, was fear of being different,” he says now. Asked if he regrets the decision, he says: “The considerations that led me and others to have our children circumcised hardly exist today. The feeling these days is that we who circumcise are on the defensive. Even if they are not exceptions, they have to defend their choice. You can no longer simply shrug off those who are against circumcision. It’s like the first vegetarian. I imagine he had a hard time at first, because he was the subject of ridicule, but then the idea spread. Nowadays, even if only 10 percent of the population are vegetarians, the others feel uneasy.”

‘Like pulling a tooth’

A third of the circumcision procedures in Israel are performed by physicians (according to unofficial data). The most popular of them perform hundreds of circumcisions every month. For the past decade, Dr. Daniel Shinhar and Dr. Ram Mazkeret have run a private clinic that performs circumcision under anesthetization. They perform three to four a day, six days a week. Shinhar is a pediatric surgeon and Mazkeret specializes in preemies and infants, and also underwent training in the religious aspects of circumcision from the Movement for Progressive Judaism (Reform).

“The reason we do the circumcisions together is that one of us holds the baby and the other does the procedure. We do not tie the baby as is done in religious circumcisions, because tying causes him discomfort,” says Shinhar, adding that most of the parents who come to them are secular Jews. A few are from the religious Zionist movement and even fewer are Muslims.

“The main difference between a physician and a mohel is that we are allowed to inject an anesthetic and a mohel is not,” Shinhar adds. “Medical studies show that the pain of circumcision is equal to that of having a tooth pulled without an anesthetic. We tell people who are uneasy about the anesthetic that they should have their son circumcised without an anesthetic only if they agree to let me pull a tooth without an anesthetic.

“In addition,” he adds, “it has been found that infants who undergo circumcision without an anesthetic develop posttraumatic manifestations in the first six months of their life. They are more irritable, cry more and get stressed from minor stimuli.” Another difference lies in the fact that in a medical circumcision, the mother is allowed to hold the baby during the procedure, which, according to the physicians, is calming for both mother and baby.

The Shinhar-Mazkeret clinic consists of a large room in which a religious ceremony is held for those who wish to have one, and an adjacent smaller room where the parents and grandparents are permitted, for the operation itself.

“The separation between the rooms is meant to envelop the baby in a quiet, calm atmosphere. The banquet halls [where most circumcisions are held, followed by a meal] usually add more elements of pressure and noise,” they explain.

Shinhar also performs circumcisions at a later age, but notes that doing the procedure at the age of four or five, for example, constitutes “a significant trauma for the child, because he remembers it.” At those ages the procedure is done under a full anesthetic and with stitches. Most of his older patients are new immigrants from Russia who did not undergo circumcision in infancy.

Physicians such as Shinhar and Mazkeret are under the supervision of the Health Ministry but not of the committee that oversees the mohelim – it deals only with those who perform the ritual according to Jewish religious law. The committee consists of clerics and Health Ministry officials. Its principal task is to supervise the training of the mohelim, who study many religious laws, such as the permitted length of the fingernail for peeling off the foreskin.

Mohelim are not authorized to inject a local anesthetic or to stitch the skin if a blood vessel is cut. Nor do they have to perform the circumcision in a sterile environment. The result is that an ostensible medical procedure is done in the conditions of a banquet hall. The committee has the power to revoke a mohel’s license if he caused damage during the procedure or behaved negligently.

“The moment a mohel encounters a complication, we as physicians are obliged to report it to the Health Ministry, which in turn informs the committee that supervises mohelim. It then examines whether this was a chance complication or part of a series,” Shinhar says. “The committee has the right to strip a mohel of his license, but I cannot recall a single case in which it did so.”

The AIDS controversy

Numerous studies exist about the medical implications of circumcision and non-circumcision, but all of them, without exception, need to be qualified. It is difficult to study thoroughly phenomena relating to sexual relations, sexual diseases and aesthetic preferences when the foreskin, or its absence, is isolated from other factors. Indeed, it is impossible to attribute with certainty various diseases, behavior or social phenomena to the presence or absence of the foreskin.

For example, how can research that says the chances that a circumcised man will contract AIDS are 60 percent lower than those of an uncircumcised man (as per a 2007 WHO study), explain the fact that in the United States there are more circumcised men − but also proportionally more cases of AIDS − than in the Scandinavian countries?

In any event, it is worth dwelling on research relating to the connection between circumcision and AIDS. The subject is particularly interesting because a consensus exists among both advocates and opponents that circumcision does reduce the risk of contracting the disease. The key debate, then, is over the question of whether circumcision represents a solution per se to the AIDS epidemic.

Proponents of circumcision claim that it reduces the prospects of contracting the disease and can therefore help reduce its spread. The approach of the opponents is reflected in Galit’s question: “Am I supposed to tell my son that because we circumcised him and reduced the chances that he will get AIDS by half, that he can use a condom only once every two times he has sexual intercourse?” In short, she says, this is a ridiculous argument.

Tamir, for her part, wonders what will happen if an anti-AIDS vaccine is developed in 10 years’ time. “How will I feel about having cut my son’s sexual organ in order to reduce the likelihood that he will contract AIDS when there is already good nonsurgical protection available (the condom) and in the end a vaccine will also be developed? It’s just an excuse to go ahead with circumcision, not a real reason.”

Rotem (not his real name) is a researcher in the medical sciences. He had his month-old son circumcised “for cultural reasons,” he says, “and not because of medical reasons of one kind or another. There is really no medical reason for circumcision. Even if it reduces AIDS, I will recommend to my son, when the times comes, to use a condom. Just as we do not take out the appendix to prevent appendicitis, or pull out the infant’s fingernails so he will not scratch himself − we should not tell ourselves that we are having a circumcision done in order to avoid AIDS. Let no one lie to himself.”

Another point related to the circumcision-AIDS nexus is what Ido calls the “post-colonialism of the cock.” He’s referring to the phenomenon of physicians from developed countries going to African states to circumcise the natives, with the aim of reducing the spread of AIDS. (One such international organization is the Jerusalem Aids Project.)

“Every novice statistician knows that just because the risk of contracting AIDS decreases by 50 percent, that does not mean that the number of unprotected acts of sexual intercourse can be increased by the same ratio,” Ido says. “If you want to avoid sexual diseases, use a condom. Period.”

Sadeh: “I would personally prefer the money being spent on the circumcision project in Africa to be used to buy condoms and for educating people to use one every time they have sex. I believe that it is ethically wrong to call for cutting off part of a healthy body in order to statistically reduce the likelihood of falling ill with a particular disease. To do sweeping harm to a whole population so that a few of its members will be spared randomly is an example of distorted reasoning. No one would dare put forth such an argument in any context other than male circumcision.”

The question of whether circumcision affects sexual pleasure is also unresolved. “All my life I have treated my circumcised sexual organ as something natural, as though this is how I was born,” Sadeh says. “But when I looked into the subject in connection with my son, I reached a point where I could no longer avoid thinking about myself, about how my body was mutilated. It was a horrific experience which even women who are against circumcision are incapable of understanding. It is hard for a man who underwent circumcision to internalize fully the meaning of the loss. The part of my sexual organ that was cut off contains the highest and most sensitive concentration of nerves on the penis. The foreskin is a third of the skin of the sexual organ and in the adult male reaches an average size of 10x15 centimeters. That is a tremendous amount of pleasure-making skin that is lopped off.

“Today I realize that my parents caused me to have a scar on the sexual organ. It’s hard to be understanding about that. Suddenly my parents’ rationale − that everyone does it − becomes one that I would not be capable of presenting to my son.”

Sex before and after

There is one group that can provide an answer from their first-hand experience about sexual experience: new immigrants from the former Soviet Union, who arrived in Israel uncircumcised and underwent the procedure at later ages. They had sex before and after.

Yuri, 26 (not his real name), a student at the Technion − Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, was circumcised when he was 16. “I was seven when we came to Israel,” he says. “I was not circumcised in Russia because I am not a Jew − my mother is not a Jew, but my mother’s father is, and that made it possible for us to immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return.” It was only when he was 15, Yuri says, and started to have sexual relations and confessed to his first girlfriend, a native-born Israeli, that he was not circumcised, that he started to feel there might be a problem. “I realized that having to tell about it every time anew was going to be a burden, and I didn’t want to have to deal with that,” he says.

Yuri asked his mother to arrange for him to be circumcised, and together they looked for a private doctor. The procedure was carried out under a local anesthetic, but contrary to what Dr. Daniel Shinhar says and to the prevailing opinion, Yuri does not recall the event as traumatic. He went back to having sex with his girlfriend, but then realized that “the feeling in the sexual contact was affected, it was wrecked. There was a great deal less sensitivity and I needed a higher level of stimulation to reach erection. Two years ago, when I entered the Technion, the subject started to bother me. I am a person who often looks back, and unfortunately I cry over spilt milk. I understood unmistakably that I had made a mistake. I was 16 and I was an idiot.”

Yuri did army service, but says that did not affect his decision; it was only a kind of “bonus that accompanied the choice.” Looking back, he says, “I tell myself that it’s inconceivable that people of such low quality as those with whom I served in the army should influence decisions related to my body. The only thing I can say to my satisfaction is that the army was not a consideration.”

Would you recommend to parents to have their children circumcised?

“If there is no medical problem that makes it necessary, then no.”

Circumcision in Islam

The custom of circumcision in the Arab world is a “condition of acceptance” to Islam. It is performed at different ages. (In Israel, most of the male Muslim population undergoes circumcision at infancy.) Because the precept is not mentioned specifically in the Koran, some scholars have argued that the roots of the custom lie in pagan Arab culture. Others emphasize the circumcision undergone by Ishmael, Abraham’s son − or the declarations by the prophet Mohammed with respect to the commandment − as forerunners of the custom. According to one belief, the prophet Mohammed was born without a foreskin, and accordingly the foreskin is perceived as a source of shame in Islam. (Gili Harpaz)

WHO’s counting

It is difficult to arrive at an accurate estimate concerning the scale of the practice of circumcision worldwide. However, the World Health Organization estimates that about 30 percent of the world’s males undergo circumcision (of whom 70 percent are Muslims).

Among Jews the number is close to 100 percent of all males, and among Muslims more than 90 percent. There are high rates of medical circumcision in South Korea, where 85 percent of males are circumcised (the custom there was adopted from the United States in the 1950s); in the United States and Australia, about 60 percent are circumcised, though this has seen a downward trend in the past decade; and in Canada about 25 percent of men, also with a downturn. In Europe, South America and Asia (apart from South Korea), less than 1 percent are circumcised for religious reasons. In addition to Jews and Muslims, the circumcision as a religious custom is also widespread among tribes of Africa, Australia and America.

Circumcision in Judaism

In Judaism, every father is commanded to circumcise his son on the eighth day after his birth. The brit milah ritual symbolizes the covenant between God and Abraham, who circumcised himself. The covenant continues to be perpetuated by circumcising “the seed of Abraham.”

Additional significance is also attributed to circumcision. Maimonides, for example, writes, in the third part of “The Guide for the Perplexed” (translation: Shlomo Pines, University of Chicago, 1963): “Similarly with regard to circumcision, one of the reasons for it is, in my opinion, the wish to bring about a decrease in sexual intercourse and a weakening of the organ in question, so that this activity be diminished and the organ be in as quiet a state as possible ... In fact this commandment has not been prescribed with a view to perfecting what is defective congenitally, but to perfecting what is defective morally. The bodily pain caused to that member is the real purpose of circumcision. None of the activities necessary for the preservation of the individual is harmed thereby, nor is procreation rendered impossible, but violent concupiscence and lust that goes beyond what is needed are diminished. The fact that circumcision weakens the faculty of sexual excitement and sometimes perhaps diminishes the pleasure is indubitable ... Now a man does not perform this act upon himself or upon a son of his unless it be in consequence of a genuine belief. For it is not like an incision in the leg or a burn in the arm, but is a very, very hard thing.” (Gili Harpaz)

Cut from the ballot

In the United States, circumcision became popular in the mid- to late-19th century as a medical operation aimed at preventing masturbation, which was thought to spread disease and cause madness. Another reason was to avert diseases such as penile cancer and infections of the urinary tract. Presently, medical circumcision is usually performed by physicians on the second day after the baby’s birth. Between 1999 and 2010, there was a decline in the number of circumcisions across the country (some data suggest a decrease of more than 50 percent). The reasons could be a growing campaign against the custom or cessation of funding for circumcision by the federal government, which forces parents to pay for the procedure themselves.

In May 2011, the subject hit the headlines when a proposed referendum in San Francisco, calling for a ban on circumcision, obtained the necessary 7,700 signatures to put the issue on the ballot. Under the proposed legislation, performing circumcision on anyone under the age of 18, including for religious reasons, would be a misdemeanor carrying a fine of $1,000 or a year in prison. The referendum was to be held in November 2011, but in July San Francisco Superior Court Judge Loretta Giorgi ruled, as ABC reported, that “the measure to criminalize circumcision must be withdrawn from the November ballot because it would violate a California law that makes regulating medical procedures a state − not a city − matter.” The legitimacy of circumcision and its consequences have been the subject of debate in the United States for years. Nor is it surprising that the proposal came up, of all places, in San Francisco, the capital of the American gay community, many of whose members, including Jews, have come out publicly against the circumcision custom.

The gay community was joined in this case by Reform and Conservative Jews around the country, who are opposed to circumcision. The most vocal of them is Miriam Pollack, a member of a Conservative synagogue in Boulder, Colorado, and a lecturer who speaks wherever possible about the sin of circumcision. The movement against circumcision in the United States is called Intactivism.

Beauty mark

The “aesthetic argument” in favor of circumcision encompasses two groups. The first consists of men and women who think that a circumcised penis looks better; the second of men who want their children to look like them. Until the 19th century, the Western world viewed an intact penis as the essence of male beauty − as artwork over the centuries suggests. Figures such as Jesus or David were probably circumcised in real life, but the sculptures of the time show them with foreskin, based on a perception that this is the proper representation of beauty. Aesthetics, though, is not an absolute; it changes in accordance with time and place.

Many fathers who have their sons circumcised express the desire that they will not look different, adding that they are happy to have been circumcised and accordingly are happy to pass on the custom to their children. To this Galit responds, “My children never asked me why they are different from their father. Since when do children have to be exactly like their parents?”

Riki, from Petah Tikva, adds that the issue of similarity and difference “raises the question of whether brunette parents who have a redheaded boy have to dye their hair brown in order to resemble them.” Ido’s mother recalls a children’s book she encountered in Britain which explains the human body to children. Bodily organs are shown in a variety of colors, shapes and sizes, and the children are asked to point to the illustration which most resembles them. The chapter on the genitalia had four different illustrations of male sexual organs, two circumcised and two not. The children are asked, “Which picture looks most like what you have?”

“A book like that could make Israeli children more tolerant,” Riki says. “I tried to get it published here, but was unsuccessful.”

Religious act

A spokesman for the Health Ministry stated: “Circumcision is not considered a surgical procedure in Israel but a religious act. Accordingly, the conditions for performing it are under the responsibility of the Chief Rabbinate. There is a meticulous system of authorization. An authorized mohel (ritual circumciser) is under close supervision by an inter-ministerial committee (on which the Health Ministry is represented). This covers formal authorization, general behavior, professional behavior and more. There is no threshold level for the activity of a mohel. A mohel does not receive medical training; the profession is handed down from one person to another without any supervision or prior conditions with respect to medical knowledge. There is a threshold condition for receiving authorization and there is instruction and tests in medical subjects which are under the rabbinate’s responsibility.”

The response of the Chief Rabbinate:

“To receive formal certification as a mohel, the candidate must meet rigorous conditions, including receipt of a medical certificate confirming that he is mentally and physically healthy, proof that he has undergone a test by an optometrist and has received a series of vaccinations against hepatitis B, and so on.

The medical subjects about which the candidate is tested in order to be authorized as a mohel are: genetic diseases (about which the child’s parents must be asked), symptoms of illness in the newborn, medical reasons for delaying the circumcision, composition and function of each component of the blood, blood-related problems, hepatitis in the newborn, possible complications of circumcision, hemorrhaging, cessation of bleeding, clotting, diagnosing and treating shock, infections, inflammation and many other subjects. A candidate who successfully passes an examination receives a certificate for just one year. Toward the end of the year, the mohel must again pass a professional examination administered by a supervisor on behalf of the committee [of clerics and Health Ministry officials that oversee mohelim], and also undergo a medical examination.”

In response to the article in general, the Chief Rabbinate stated: “As long as religiously observant physicians perform the circumcision according to the rules of Jewish law, they will be blessed.”

-------------------------------

Tweet

Follow @OregonNews

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Articles for June 17, 2012 | Articles for June 18, 2012 | Articles for June 19, 2012

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Salem-News.com:

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2025 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.