Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Jan-15-2013 21:17

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Stateless: When Nothing has Changed

Jennifer Fierberg with Scott Erlinder Salem-News.comScott Erlinder documentary explains the challenges many refugees will face.

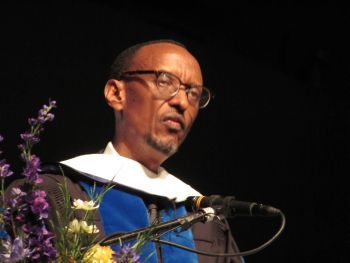

Rwandan President Paul Kagame. Photo by Jennifer Fierberg Salem-News.com |

(WASHINGTON DC) - In June 2013 the UNHCR has determined that the Cessation clause for Rwanda shall be invoked on all refugees living outside of Rwanda. In order to invoke this clause it has to be determined that the reasons people fled a country no longer exist.

Scott Erlinder |

For example, in 1959 thousands fled an oppressive regime when the monarchy was abolished due for fear of being killed for their ethnicity. The same thing happened again during other country wide uprisings and ethnic domination's. The most recent case is that of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide.

According to UNHCR in 2011 over 115,000 Rwandan refugees remain outside of the country and many continue to flee daily due to the oppressive conditions that remain despite the UNHCR declaration that these situations don’t exist.

While the immediate threat of being killed in genocide may not be a present threat there are many other reasons people continue to flee that the UNHCR is ignoring despite the piles of reports documenting the human rights violations that continue daily inside Rwanda.

Rwanda is second only to Uganda in their pursuit to bring refugees home. On the surface, to many non-refugees, this move may appear positive and hopeful but to the many refugees who fled persecution and death this move is quite unsettling.

The majority of the developed world will never know what life is like as a refugee. Many have been imprisoned for no legal reason upon arrival in safe-haven countries prior to being able to obtain refuge. Some have been held in jails for up to a year without just cause. For refugees, the term “guilty until proven innocent” is a common experience.

One refugee told this writer that being a refugee often feels like being no better than a used piece of toilet paper. While these emotions may beg the question “why not go home”? In Rwanda, however, this question is a complex set of deadly and problematic circumstances that history has proven over and over again.

In a recent documentary on this cessation clause, Scott Erlinder explains what is happening with this clause and the challenges many refugees will face.

In a one on one interview, Mr. Erlinder answers some questions about his film:

JF: What prompted you to make this documentary?

Peter Erlinder |

SE: I was in the middle of a project to send cameras to indigenous people and refugees to let them tell their stories and give them a voice. Some of these stories came from Rwanda refugees.

As you and some of your readers know, my brother, Peter Erlinder, was deeply involved with defending people accused of Genocide and war crimes with the International Criminal Tribunal on Rwanda.

Over time I had heard his stories and was interested in the progress of the trials, but when the Rwandan government arrested my brother, obviously this got a bit personal. I wanted to know what my brother had done to be branded a “Genocide Denier”, which I never heard him say.

While we were not close, I did know of his great work defending those who the “system” had marginalized- be it in the US or at the ICTR.

As more and more testimonies came in from the refugees, along with what my research was telling about the Rwandan government of Paul Kagame, it became clear that not only did the refugees have well founded fears, but that the numerous attempts by the UNHCR and many host states to implement repatriation of the refugees had been consistently ill planned.

JF: How has it been received by the public?

SE: The response has been great! The film is in pre-release and is 99% done. We wanted to get the film’s message out as soon as possible, so we did the pre-release. The content is all there for the viewer, we’re just cleaning it up a bit for broadcast. There are a lot of “techy” things they require.

JF: Did you face any obstacles or dangers while covering such a sensitive subject?

SE: Personally, I didn’t have any dangers; the people who did are all the intrepid refugees that risked a lot to get the footage to make the film. I just helped them along with training and the final story and edit. Obviously, production took a while because of the Africa-America connection, but instead of being a “helicopter documentary”, where one flies in for a week or two, shoots and leaves, I felt the approach of the letting the refugees have the say was a better approach.

JF: Has there been any negative impact toward anyone featured in the film since its release?

SE: Actually, no, I haven’t heard anything as of yet. We didn’t proclaim anything that was not documented on the net or by the UNHCR.

JF: With Rwanda being, basically a police state, how were you able to get footage inside Rwanda?

SE: There were many people who got us this footage. Some were Rwandans, some were visitors. Obviously you just don’t go and plunk down a camera anywhere you want, but the more people that submitted footage, the more we were able to craft the film. Sometimes it’s that one surreptitious shot that says it all. Also, the miniaturization of cameras has made this possible. Technology is neutral, how you use it isn’t. The Rwandan government has been very good about using it to their benefit, so I helped the refugees fight back in other ways.

JF: I understand that after you published the documentary one of the featured interviewee’s asked that her interview be removed from the piece. What happened and why did she request this?

SE: I have to say we made one major rookie mistake. In the rush to get the film out, my editors misnamed a person. She also stated we misplaced her story in the “timeline” of the film. The name was certainly a mistake, though I felt the part of her interview we used was not exactly out of place, I deferred to her wishes and removed her from the film at her request. It didn’t change the fundamental story at all.

JF: Making any film is a learning process. What did you learn from making this film?

SE: Wow, that’s a big area to cover…I learned, even more than ever, the power of getting people to talk on camera. It’s hard to deny a video interview. The down side of this, as far as those under threat, is now they know who you are and what you said. Over the time it took to make the film, many refugees were attacked, some murdered (like journalist Charles Ingabire) and it takes a lot of guts to do what they did, given the possible consequences.

Regarding the issues in the film, I learned that the UNHCR on the ground level is not always a noble entity. This can be true of any organization (MONUSCO could be pointed to as well). There are ideals and then implementation and implementation depends on the character of those involved. There are a lot of great people working for the UNHCR but there are those that do take advantage. I don’t blame the organization, we need the UNHCR, I do blame some of those who create policy.

Also I learned that politics, not compassionate humane decisions drive many of the countries decisions to return the refugees.

JF: What started the process of invoking the cessation clause of Rwandan Refugees and why is this now an issue?

SE: Rwanda has been very proactive on trying to get refugees to go back since 2003. Some of these refugees have been outside the country since the 1959 independence some have been there since the Genocide.

The refugees feel this first implementation of the clause, which will affect those outside the country from 1959 to 1998, is a “nibble” approach and that further implementations will occur since this one may set a precedent.

The fact of the matter is that many Rwandans are leaving the country for both political and economic reasons. These are tied together. Don’t agree with the politics? You get no support or even have further persecutions placed on you. And this is not an ethnicity issue- both Hutu and Tutsi Rwandans are affected.

We didn’t want to bring up ethnicity very much in the film because we are for all Rwandans to have peace and equality. The only place we DID do this was in reference to the amendment to the constitution, done in 2008, which specifically mentions ethnicity. This seems to be contradictory to the pronouncements of the Rwandan government which has outlawed ethnicity.

JF: What indicators have the UNHCR used to determine that there is no threat in Rwanda anymore and it is safe to return home?

SE: This is a very good question, and one I don’t have any precise answer for. It was also the reason for doing the film. Anyone doing a little research can see that while economic developments are touted, human rights have not, in UNHCR speak, been manifest into “permanent and durable solutions”. If you just look at the events surrounding the 2010 elections, this becomes obvious. Murder, intimidation, arrests, etc. It’s all there for the UNHCR to see.

JF: Is this a replay of what happened during the final years of Habyarimana’s regime?

SE: I don’t think this is a replay of the Habyarimana regime. I would think you could call it a new “variation”. While the Habyarimana regime was certainly repressive, we forget that it was not only repressive to Tutsi, it was repressive to Hutu in the south, so it was it’s own “clique”. People tend to think that Hutu and Tutsi were equal numbers in the population, but they were/are not. The proportion of Tutsi is about the same as the African American population to the Caucasian population in the US. (15-17%)

What has happened in Rwanda is a very small portion of Tutsi refugees, raised in Uganda since independence, have control of all the levels of government. They discriminate against their own kind because they may not agree with them- Deo Mushaydi, imprisoned for life, is a perfect example or Dr. Theogene Rudasingwa. The list grows day by day.

Where there is a similarity is in the increased tensions in the country and a new diaspora of Rwandans just like what happened in 1959. The cutting off aid to Rwanda could be called a similarity. We, the world, have to be very careful that we don’t create a “perfect storm” of economic problems that helped push the country to conflict like it did in 1990- which ultimately led to the Genocide. This does not, however, mean we, the world, have to put up with a repressive government so we have “stability”.

| Stateless No 2 from Scott Erlinder on Vimeo. |

The one big difference right now is that you have Rwandans who do not want to go back. This is a fundamental difference from the RPF history that said they wanted to return to their homeland and who invaded in 1990 to create a democracy and equality.

JF: What can people who watch this documentary do to help stop the invocation of the cessation clause?

SE: The main thing people can do is to write to the UNHCR,

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Case Postale 2500

CH-1211 Genève 2 Dépôt

Suisse.

+41 22 739 8111 (automatic switchboard)

+41 22 739 7377

|

Jennifer Fierberg is a social worker in the US working on peace and justice issues in Africa with an emphasis on the crisis in Rwanda and throughout the central region of Africa. Her articles have been published on many humanitarian sites that are also focused on changing the world through social, political and personal action.

Jennifer has extensive background working with victims of trauma and domestic violence, justice matters as well as individual and family therapy. Passionate and focused on bringing the many humanitarian issues that plague the African Continent to the awareness of the developed world in order to incite change. She is a correspondent, Assistant Editor, and Volunteer Coordinator for NGO News Africa through the volunteer project of the UN. Jennifer was also the media co-coordinator and senior funding executive for The Africa Global Village. You can write to Jennifer at jfierberg@ymail.com. Jennifer comes to www.Salem-News.com with a great deal of experience and passion for working to stop human right violation in Africa.

|

|

Articles for January 14, 2013 | Articles for January 15, 2013 | Articles for January 16, 2013

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2025 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.