Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Jan-10-2009 12:43

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Flop in Chile

Eddie Zawaski Salem-News.comWorld travels from a former Willamette Valley resident.

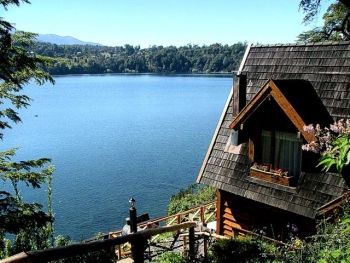

Villa la Angostura Courtesy: inmopatagonia.com |

(EL BOLSON, Argentinia) - When a person isn’t well, it’s always best to be among friends and neighbors, people who care. This thought echoed in my head as Gail and I got off the bus back in el Bolson after our difficult trip to Chile.

Once we were safely back at el Molinito, there would be the comfort of others who would help you to focus away from your illness and offer support, even if those people distracted you only by means of their fixations on their own problems.

Being sick on the road in a foreign country is no picnic and we were glad the trip was over.

For some time, we had been looking forward to this trip to Chile. People had told us that on the other side of the mountains the climate was just like the Willamette Valley, lush, green, and mild.

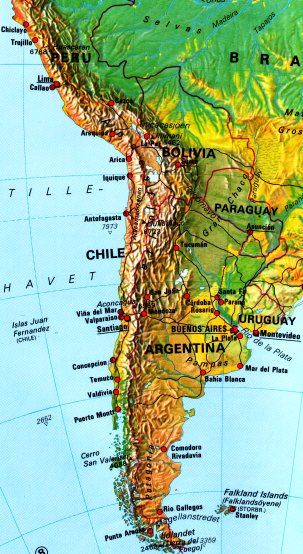

We were also anxious to get a look at the sea: it had been a long time since we’d sniffed the salt air of the Pacific. Going to Chile was business, too, as a hop across the border would allow us to renew our tourist visas which were only a week or so from expiring. So we were in high spirits when we boarded the highway cruiser from Bariloche about 2:00 PM one Thursday afternoon.

Just as soon as the bus pulled out of the terminal, I began to experience the first hint of an upset stomach. It was nothing definite, but just enough queasiness to cause me to refrain from reading on board, as I wouldn’t want to add another risk factor to losing my lunch. Thus, I was content to look out the window as we glided around the east shore of Lake Nauel Huapi and then took the westerly turn through the forest on the north.

As the bus wound around the many curves on the road to Villa La Angostura, the uneasiness in my gut strengthened into definite nausea. I was glad that my lunch was more than four hours old and probably out of my stomach by now.

We only got a glimpse of Villa la Angostura (Lobsterville) from the bus window. It appeared to be about the same size as el Bolson, but more heavily forested and more upscale. The downtown core was about three blocks long and lined with newer Patagonia rustic style buildings. The main drag ran along along a little ridge so that on either side you could look down at streets that ran down into the forest or down to the lake lined with cedar chalets. Even on a dark and drizzly day with slushy snow beginning to fall, it was easy to see that this place bristled with prosperity. The bus made a short stop here for gas and then continued on up the road to the border.

At the Argentine border post, things began to become a bit more difficult. It was cold and wet when everyone piled out of the bus into the immigration office. In typical Argentine fashion, there was no line or apparent order to things as everyone simply milled about in the office vestibule as the officers called out our names from a list they had been supplied by the bus company. I suppose this only took a few minutes, but by this time, I had developed a headache and my bones were beginning to ache. I got very very cold waiting in that room and was happy to have my name called and my passport stamped so I could get back on the bus.

From the Argentine to the Chilean border post, it’s about an hour’s drive over a mountain pass that tops out at 1321 meters (4100 ft.). On this particular early June afternoon, the first snow of winter was lightly falling. The road is nowhere particularly steep, but it is everywhere curvy.

At one curve, near the summit, I noticed an oil tanker truck turned on its side at the margin of the road with it’s red and orange hazard lights blinking helplessly in the thin blanket of snow. I was careful not to point this out to Gail. Seeing it hadn’t made me feel better and I didn’t think it would do her any good either.

As the bus rolled around the icy curves, I felt colder and colder. I put on my gloves and huddled up as best as I could, but it was fever, not actual cold, that was taking its toll. It seemed to take forever to come down the west side of pass into the dark and finally to the end of the snow zone at Punto Pajaritos (little birdies point), Chile. This is where the fun began.

Unlike Argentines, Chileans take border crossings seriously. The bus driver informed us to pile out with our hand luggage and drop our bags on a conveyor that would take them through a scanner. Running all the baggage through the scanner took quite a while as the Chilean customs officers managed to find reasons to open every third bag or so, rummaging through each one roughly before resuming the search. Gail’s bag happened to be one of the ones they chose for closer inspection. When they did, they found contraband and there would be hell to pay.

It seemed that the fruit that Gail had packed for the bus trip was not allowed to cross the border. A very stern red-faced, blue-eyed, crew-cut official dressed in a uniform that looked more Whermacht than South American customs lectured us as he pulled out each banana and pear. Gail shrugged off his admonitions with a desultory allusion to the fresh fruit lunch he would soon enjoy and walked off with her now lighter bag. As she strolled toward the customs house, the official began calling after her loudly, “Senora! Senora!” but she didn’t hear or, more likely, thought he was yelling at someone else. Through my feverish haze, I could see that with each “senora!” he was getting more agitated. I imagined that he was about to vault the conveyor and chase her down. I mustered all my remaining strength to call out her name to come back to the counter. I myself had once spent time locked in a small room surrounded by Turkish customs police who weren’t happy about my paperwork and didn’t want Gail to suffer the same indignity.

The customs man was angry about her not having filled out a customs declaration and was waving a blank form for her to fill out. Had it been the Argentine side, they would have filled the form out for her and offered a sip of mate before going on. Here in Chile, getting shot is not out of the question.

Inside the immigration office, the bus driver was busy calling each passenger to his or her place in a line, which we would progress through to get our passports and visas stamped. Despite our being out of order in the line, the younger officer at the desk stamped our passports and visas. Here in Chile, we were required to keep a separate paper visa, which would be stamped both on arrival and departure to validate our stay.

By the time this ordeal was over, I was more miserable than ever, shaking with fever and wracked with deep aching pain in the cold and driving rain. I tried to get something to drink and go to the bathroom before re-boarding the bus, but even that proved difficult. The restroom guardians would not allow me in to piss until I had bought something in the cantina and the attendant in the cantina forced me to wait while he hand-wrote a paper receipt for every candy bar, seven up, or cup of tea. It would take another twenty minutes for the customs officers to finish messing with all the stowed baggage and harassing all the poorer looking passengers. I prayed that the seven up would stay down.

The ride on into Osorno and Puerto Varas took but two hours, but was one of the longest of my life. The headache and aching in my bones made it impossible to be comfortable in my seat and the darkness made the trip seem forever. All I remember from Osorno were the modern concrete bus terminal and the proliferation of big box stores and malls at the outskirts of town.

If it hadn’t been for the numbers of people walking on the streets, we could have been back in the U.S. After losing two-thirds of our passengers in Osorno, the bus pulled out onto a freeway and headed south. We were on the Pan-American Highway, Route 5. Within an hour we would be in Puerto Varas and only a taxi ride away from the hospedaje room I’d reserved earlier in the day over the internet.

I’d picked a place that was centrally located right downtown, a block away from the lake, but I hadn’t realized the place was closed for the season. At least that’s what the host told us at the door. He had, however, fixed us up a room and would, he said, be pleased to let us stay there a few days as I had requested.

This was a good thing. I was in no condition to go looking around town for another place and was eager to lie down and take some of the medicine that Gail had gotten for me at the drugstore on the way here. I didn’t care that the place was closed. I didn’t care that the room was cold. I didn’t care that everything was painted in garish clashing colors and every floor was at a different level. With its open central room complete with sofas, recycling center and postcards from around the world on the banisters, the place looked like Eugene, 1970. Taking familiar surroundings for comfort as well as a few ibuprofens, I went straight to bed.

While my condition was improved by morning, I was still not in any great condition to explore or enjoy much of anything. The blowing rain of the previous had halted by morning, but stood waiting behind masses of low dark clouds that were dropping scattered squalls on Lago Llanquihue to the west. It was dry enough to permit a little walking around the downtown, at least enough to gain the impression that we were in a marine climate not unlike Seattle, complete with moss, ferns, rhododendrons, and hydrangea growing like weeds.

The jumbled-together wooden structures downtown gave the town a mildly anachronistic flavor and the ubiquitous German signs advertising “zimmer” for rent or “schnitzel” for lunch suggested a strong Teutonic connection. The railway station was closed to service (only to Puerto Montt) for the season, but housed a semi-permanent art exhibit of paintings that had won prizes in a local competition. All were quite impressive.

We stumbled into a bee-products store that had a nearly completed portrait of the Bagwahn Shree Rajneeesh next to the front counter, but the shop attendant denied any knowledge of the subject of the portrait.

Chileans appeared to have nicer clothes and more and newer cars than Argentines, but not better homes. The really upscale well-constructed and roomy mansions of the middle class were all scattered about on spacious plots far outside the town in a nascent sprawl unknown on the east side of the Andes. The cost of basic goods and services seemed to be about twice the rate we had become accustomed to in Argentina.

Imported goods were in greater supply, but that didn’t preclude a few knots of campesino peddlers offering produce on several street corners. We had a rather expensive dinner at a local foreigner hangout where our chef danced our food in and out of the oven and we shared the dining room with a single overweight British woman who spent the evening buried in her paperback and bottle of wine. By nightfall, I was mostly recovered from my illness, but not overly impressed with Chile so we decided to make an early exit the next day for a bus back to Bariloche.

In order to get back to Argentina, we needed to hop a local bus to Puerto Montt’s main bus terminal. It was there we found the wild, chaotic, seedy, and dirty environment we always expected but never found in Argentine bus terminals. This place was right on the waterfront, a major blot that had been left after a recent urban parquization had taken place along most of the shore of Reloncavi Sound.

After losing my appetite to the fly that lay struggling its death throes in my water glass at the bus cafeteria, we took a walk along the sound and through the downtown area. Puerto Montt’s commercial district is an amazing mixture of cheap discount knock-off stores and mega corporate chain outlets pressed against each other in a way that suggests a basic Chilean urban planning philosophy: jam everything together tightly in a small place so nobody misses anything.

Our treat that afternoon was a group of Native American street musicians from Ecuador. Despite being distorted by over-amplification, they produced a sound that was vaguely reminiscent of North American Plains Indians while singing in a language that, to me, sounded just like Lakota. With their buckskins, long flowing black hair, bone breastplates and eagle dancing, they would have looked at home on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Only the South American panpipes suggested they were Andean and even then, they played some North American flutes as well.

The bus trip back was much more pleasant than the ride down, especially since we were able to see the scenery we’d missed on the way down. Moreover, the bus was practically empty as the only other passenger was a young Korean gentlemen who complimented Gail in good Castellano and smiled patiently at the Argentine customs official who insisted that he had earlier processed the man’s brother through (another Korean named Kim). Mr. Kim was the friendliest person we had met in Chile and having him accompany us back to Argentina was a good indication of what we were returning to, more hospitality.

The folks in el Bolson and particularly at our hospedaje have been very friendly and have treated us just as if we were members of their own family. Dioniso and Noemi, the owners, have given themselves completely to us as friends, even sharing their friends and family with us. Jose Wisky and his wife, Kayla, have also taken us into their hearts and home, expanding our experience and circle of friends. Add to them the people we’ve met in various “business” contacts out in town, Marta, el Cubano, Angelica and scores of others and we feel right at home when we’re here. Let me illustrate by relating a little story about what happened just after we returned from Chile.

Having only recently returned and recovered from our arduous journey to der Chile, we were simply relaxing and reading in our room one Sunday noon when there came a knock on the door. Upon opening, I discovered a three year old girl, Julietta, holding forth a handful of chocolates. Her grandpa, Dionisio, was standing behind her to remind her to say that these candies were Father’s Day gifts. I think he was also there to be sure she actually gave us the chocolates.

After accepting the gift, we watched her run away down the stairs. A few minutes later, there was another knock. It was Julietta again. This time she had a giant box of handmade chocolate for us to chose from as she announced “Felices dia del padre,” in her tiny voice. At Dionisio’s urging, we took about twice as many of the chocolate bars as we should have and wolfed them down in no time. A few minutes later there was another knock at the door. This time it was Noemi, Julietta’s grandma, coming up to inform us that a Father’s Day outing had been organized and we were to eat our dinner quickly and get dressed to go. Diego was going to take us up to Perito Moreno, our local ski resort.

Out in front of El Molinito, Diego and his wife Miriam were busy strapping a snowboard onto the roof rack of their Korean SUV. In back in the jump seat, much to our surprise, sat Gabriela, the ghost of the Molinito kitchen. Her presence there was a tribute to the kindness and good nature of the folks here as Sylvia Plath (our secret name for Gabriela) can be quite depressive. She’s been living here at the hospedaje for about the past five or six weeks, looking for work and trying to make friends by talking about her personal difficulties.

Rumor has it that she’s turned down actual job offers in favor of sitting in our common kitchen to read Gnostic primers and report her woes to anyone who should pop in to fetch a yogurt from the refrigerator. So it seemed such a good deed to get her out even if only for a few hours. By three, all of us, Diego, Miriam, Noemi, Gail, I, Gabriela and baby Julietta in her purple snowsuit were on the road to Perito Moreno.

It’s really only about a 15 mile trip up there from el Bolson, but on the narrow dirt track that follows the upper course of the Rio Azul, it takes nearly three quarters of an hour. Since the autumn had been dry, we didn’t hit snow until we were practically right on top of the ski area. After encountering the first real snow in a large flat meadow, we turned sharply up hill and were suddenly there at one of the smallest and funkiest ski resorts I’d ever seen. The tiny parking lot with room for only about 100 cars was jammed full.

West of the lot was a rustic equipment rental shack with a pair of crossed Nordic skis over the door. Inside, the proprietor informed me that these cross-country skis were the only pair on the mountain, but that downhill skis, snowboards and minisleds could be rented by the hour or day. The tow lifts up the bunny slope of the big slope were free.

We stood and watched skiers get comfortable on their skis on the low slope and enjoyed the sight of kids careening down the sled run on the opposite hill. Julietta trekked about halfway up the sled run before making her first run with hardly a mishap.

In fact, all the children who were crashing down this hill on their little plastic rental luges seemed to have no trouble staying upright and happy. The skiers and snowboarders on the upper slope above the sled run seemed content as well. As we watched the high-altitude crowd schussing toward us, we caught a glimpse of a building, the refugio, about a quarter of the way up the slope on the right. Sensing a source of hot chocolate, I suggested a trek up there with Gail, Noemi and Gabriela.

The refugio was more crowded than the slopes below. Families and groups of friends sat around the rough-hewn tables and benches chatting, laughing and sharing mate and treats from home. The cafeteria service at the refugio bar was slow, so most people limited their purchase to a bottle of wine or a soft drink. Our hot chocolates arrived at our table lukewarm after a twenty minute wait.

Many of the faces in the crowd here in the refugio looked familiar, as we had heard that this ski area attracted no one from outside el Bolson. Sure enough, Cristina Torre, our architect, popped by our table to chat a moment about our meeting next week about our house plans. We also exchanged a few pleasantries with Sylvia Tornero, a neighborhood realtor who had shown us around to a bunch of properties, and with Gail’s physical therapist, Rafael.

The Refugio dining room was warmed not only by the huge wood-burning stove at the center, but by the company we found there. The view of the valley below and the jagged snow covered crest of Pltriquitron in the distance was a bonus. We resolved to come again with visitors ready to try out the slopes and the mate.

It was 5:30 by the time we’d slid back down the path to the parking lot where Diego already had Julietta packed into the car and was passing around the mate. Fortified by mate and cookies, we then rolled down the hill back to el Bolson at dark. The Perito Moreno ski resort had been neither grand nor impressive, but cozy, and delightfully warm. It was a family place where the family that inhabited el Bolson came to “disfrutar” (enjoy) on winter weekends. It felt good to be a part of that family.

Articles for January 9, 2009 | Articles for January 10, 2009 | Articles for January 11, 2009

Salem-News.com:

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

CHILEAN January 10, 2009 4:35 pm (Pacific time)

Excuse me, but....who the heck goes to puerto montt for its beauty? Even chileans say it! It is indeed one of the most dreadful places in Chile, however, with the best seafood.

[Return to Top]©2025 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.