Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Feb-24-2013 18:30

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

The Beatles, Love and Murder in Acapulco

Kent Paterson for Salem-News.comIn important ways, the pattern of contemporary violence in Acapulco resembles Ciudad Juarez from 2008 to 2012.

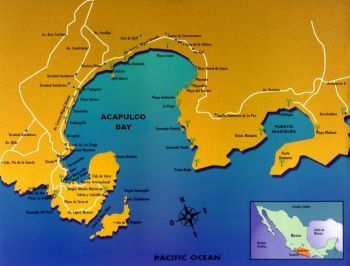

Courtesy: travel-acapulco.com |

(LAS CRUCES, NM) - There was something almost reassuring in hearing the Beatles’ “All You Need is Love” rising from the bus sound system as the driver lumbered into what has now been tagged as the world’s second most murderous city. Indeed, the sounds and images of the Fab Four kept surfacing in the sea of red roses, balloons and “I Love You” messages in English that innundated Acapulco, Mexico, during "The Month of Love."

For the sake of “Peace and Harmony,” the local and state governments even sponsored a Beatles tribute performance at the majestic, open-air concert venue near the cliffs where divers make death-defying leaps and above the sea cave where Tarzan once reputedly wrestled a giant octopus.

This year’s love-fest unfolded amid the sobering news that Acapulco had achieved the unenviable status of proportionally having the second highest rate of homicides in the world.

Based on Mexican government statistics, the ranking was assigned by a Mexico City-based non-governmental organization, the Citizen Council for Public Safety and Criminal Justice, which found that Acapulco’s 1,170 murders last year came out to 143 homicides per 100,000 people. Nationally, Acapulco surpassed Ciudad Juarez in the murder rate category and internationally was only bested by San Pedro Sula, Honduras, which tallied 169.3 murders per 100,000 population in 2012.

Acapulco’s population of almost 820,000 people is roughly equivalent to that of El Paso County, Texas.

Governing an entity that is still economically dependent on tourism, the state administration of Guerrero state Gov. Angel Aguirre denounced the Citizen Council’s ranking as a flimsy attempt at “damaging the public image of the state and the people of Guerrero,” despite the fact that the Citizen Council’s numbers were drawn from the official National Public Security System.

It’s not hard to find people who’ve suffered personal encounters with crime and violence in Acapulco. One resident who was fearful of having his name published, recounted to FNS how he watched two killers shoot a man in the head and then sick a dog to rip the victim’s throat apart. “Violence is bad,” the resident dead-panned. “You can’t go out with confidence.”

In different conversations, a taxi driver said he had been robbed five times in six years while another cabbie explained that the empty space on his dash board was where his car stereo rested before it was stolen after he parked the taxi one day. The driver added that he had a distant-in-law who was kidnapped, murdered and then dumped in a trash bin, even though the victim’s relatives paid a ransom.

“What’s going on is worrisome,” said restaurateur Laura Caballero, president of the Costera Established Merchants Association (ACEC). “We never imagined seeing decapitations or people with skin ripped off their faces.”

While crime and violence cut across all strata of society, delinquency in Acapulco is not exactly an equal opportunity employer and finds its victims and victimizers based on class, age and geographic location.

Acapulco’s famed tourist strip, the Costera, is arguably as secure as any other tourist destinations in Mexico. Essentially, the Costera has been militarized as part of Operation Safe Guerrero. Day and night, hundreds of Mexican marines, soldiers, federal police and state cops patrol up and down the big bayside boulevard in an impressive show of force. Heavily armed and wearing bullet-proof vests, they ride in the latest trucks and armored vehicles.

Dr. Sergio Salmeron, general manager of the Playa Suites Hotel on the Costera, shook his head no when asked whether Acapulco was an unsafe place to visit. “One cannot deny the facts, but security is improving in the city,” Salmeron said in his office. “The government is working on making the situation better not only for tourists but residents as well.” Asked his opinion on Operation Safe Guerrero, Salmeron said the multi-agency campaign could be better but was “functioning.”

In important ways, the pattern of contemporary violence in Acapulco resembles Ciudad Juarez from 2008 to 2012.

In both cities, violence spiked after the initial deployment of large numbers of troops and federal police. And in both places, violence largely receded to working-class districts after high profile incidents in commercial centers and heavily-transited public thoroughfares threatened to paralyze a major city. Unlike the pitched battles which have broken out in Tamaulipas or Zacatecas, the killing in Acapulco is done on a small but constant basis, a pattern which also characterizes Ciudad Juarez- one victim here, two or three there.

Historically, the City on the Bay of Santa Lucia has had a dual identity. On one side, there is the former jet-setting glitter of the Costera and Punta Diamante, and on the other the sprawling, heavily-populated neighborhoods in the hills surrounding the city where the workers and lumpen-proletariat reside.

A divide delineated by class and economics is also shaped by crime and violence. After three years of what some experts term hyper-violence, the location of the next crime scene in Acapulco is almost predictable-Colonia Emiliano Zapata, Ciudad Renacimieto, Mozimba, Coloso, and other rough-and-tumble areas of town.

A review of murder reports in three local newspapers-El Sur, El Sol and Novedades- from February 13 to February 23 samples the geography and demography of murder in Acapulco.

In the 12-day day period examined, 32 people were reported murdered. Virtually all the killings took place in working class zones or in the poor rural section of the municipality outside the city limits.

On Thursday, February 21, two men were executed in front of startled restaurant diners who were slurping down pozole on a day when locals traditionally gather to savor the hominy stew along with a musical or transvestite show. Besides the Pozole Thursday double-murder, most of the homicides in the recent period examined bore the hallmarks of gangland-slayings, though a femicide, a drunken brawl and a robbery could have explained three of the murders. The victims included 25 men, 6 women and one of unidentified gender. The news accounts listed mechanic, auxiliary cop, taxi driver and bread peddler as among the victims’ occupations. At a glance, the slain were small fish in a big, swirling pond of crime.

Roger Begeret, director of the post-graduate program of the School of Tourism Studies at the Autonomous University of Guerrero, said that young men stand out as the murder victims. An obsolete tourism economy, Bergeret contended, is generating more poverty than employment and income while a sucking a good number of young people into the pits of delinquency.

In an interview with El Sur, the local commander of Mexican troops involved in the Operation Safe Guerrero blamed the violence on disputes between criminal organizations, which number anywhere from six to 14in Acapulco, according to different sources. Allied with larger cartels, the local crime bands are difficult to control since they are “constantly mutating,” said General Fausto Lozano Espinoza, commander of the Ninth Military Region.

According to General Lozano, the struggle for dominance of the street-level drug market as opposed to smuggling routes fuels the violence in Acapulco.

“The groups are fighting over the territory of consumption, because street sales are the real productive business for them,” General Lozano was quoted.

Acapulco’s Murder City designation came fast on the heels of another scandal that shook the local, national and international scenes. The reported rapes of six Spanish women at Playa Encantada (Enchanted Beach) southeast of Acapulco February 4 triggered a crisis in damage control as tourism industry boosters contemplated the evaporation of what little international visitation remains in Mexico’s pioneering vacation destination-just as the old resort was beginning to show some signs of recovery.

The Playa Encantada crisis deepened when reports surfaced that at least two Mexican women had been raped in the same general area as the Spanish women in the weeks prior to February 4. The zone in question is actually located some distance from Acapulco’s city limits.

In fast order, the Mexican Congress, state and national leaders and dignataries of all stripes issued sharp condemnations of the Playa Encantada rapes. In an unusual move, the Guerrero State Congress formed a special commission to monitor the case.

Grupo Aca, a civic association of prominent local citizens, published a display ad expressing “profound shame for having incompetent authorities in terms of public security,” and demanded the resignations of the top officials in charge of public safety in Guerrero.

As the political heat reached a boiling point, six suspects were arrested as the probable culprits of the Playa Encantada rapes.

The Murder City-Playa Encantada crisis exploded as other looming public security scandals bubbled away in the background.

After he assumed power late last year, Acapulco’s new mayor, Luis Walton of the Citizen Movement party, declared that he encountered a municipality sunk not only in a debt estimated in the $200 million range, but five city departments infiltrated by organized crime, including the office that maintains property tax records and assessments. Walton publicly vowed that his admnistration would pursue civil and criminal charges against the persons responsible for the debt. So far, no charges have been filed.

In recent days, news media have reported a large amount of equipment missing from the municipal police department, including bullet-proof vests, more than 200 firearms and 20 patrol cars.

Walton took office after the conclusion of the Anorve-plus administration of 2009-2012, which held power precisely during the years when violence spun out of control.

Twice during his short mayoral administration, Manuel Anorve requested a leave of absence to run for higher office. First denied the Guerrero governor’s seat by the voters, Anorve later was elected to Congress in the proportional representation slot that doesn’t require majority voter approval.

The former Acapulco mayor now serves as the vice-coordinator of President Enrique Pena Nieto’s PRI party in the lower house of the Mexican Congress. Three other individuals served as interim mayors of Acapulco-Jose Luis Avila, Alejandro Porcayo and Veronica Escobar-during what was supposed to be Anorve’s three-year term in office,

While the Murder City and Playa Encantada episodes succeeded in diverting attention away from the municipal governance scandals, some are not forgetting Mayor Walton’s politically-explosive statements.

At a February 16 press conference, the ACEC announced it was organizing a protest suspending the payment of city taxes until the criminal infiltration issues raised by Walton were clarified.

“Where are our taxes going?” asked ACEC President Laura Caballero. “To organized crime?” Obdulio Izquierdo Ortiz, the ACEC’s lawyer, said he would seek a legal order sanctifying the temporary withholding of tax payments.

“We want a suspension of payments until we know what’s going on,” Izquierdo added. The attorney said the protest’s tactics were inspired by civic protests in the state of Chihuahua against election fraud in the 1980s.

As in other Mexican cities and towns, the crisis of violence in Acapulco has also sparked serious human rights concerns.

In an interview with FNS, Ramon Navarette, Acapulco regional coordinator for the official Guerrero State Human Rights Commission (Coddehum), acknowledged there had been a surge of local complaints against the Mexican army in 2011, when more than 30 complaints were filed with his office, but that the number dropped to six last year.

Navarette said his agency has an ongoing working relationship with the army that includes the holding of human rights workshops and meetings twice a month to discuss issues of common concern.

“We are very open with each other,” Navarette affirmed. “There is no limit to the questions and the answers.”

Generally, however, complaints related to the conduct of the armed forces are channeled to the National Human Rights Commission in Mexico City, he said.

According to Navaratte, Coddehum’s Acapulco office saw an overall increase in local human rights complaints from 175 cases in 2011 to 280 in 2012.

Adding that his office was in the process of compiling a final report for 2012, Navarette said that the complaints included approximately 45 cases against the Acapulco municipal police, 35 against the Guerrero State Ministerial Police and 25 against the Federal Police. Mostly, the alleged violations involved arbirtary detentions and illegal searches, according to the human rights official.

“We want (law enforcement) results in the city just like everyone else does, but we want security with human rights,” Navarette said. “We are concerned that in looking for delinquents, homes of people who have nothing to do with crime are being searched.”

In the broad scheme of things, Navaratte agreed that Acapulco’s public safety troubles are intertwined with joblessness, the lack of public services and economic deprivation in the working class sections of the city. “Poverty is the greatest violator of human rights,” he argued.

As Frontera NorteSur was going to press, another posible scandal with international implications was emerging in Acapulco in the wake of the February 23 murder of Jan K.M. Sarens, a 59-year-old Belgian national, in the glitzy Punta Diamante zone where the Mexican Tennis Open is scheduled to start this coming week week.

The preliminary accounts of the crime reported that Sarens was shot to death in his Mercedes Benz automobile in an afternoon attack while leaving a supermarket located almost across the street from where the Tennis Open is planned.

ccording to the Guerrero state government, Sarens resided in Mexico City where he worked for the SRNS Latinoamericana company.

Sarens did not fit the profile of the typical Acapulco murder victim. Information culled from the web links Sarens’ Mexican company to Belgium’s Sarens Group, a world-wide outfit specializing in industrial transportation and maintenance in the petrochemical, nuclear, mining and energy fields.

“The institutions of the three orders of government that participate in Operation Safe Guerrero have implemented an operation to nab the responsible parties of the (Sarens) crime,” the state government said in an official statement. “The Guerrero state attorney general’s office will inform public opinion of the progress in the investigations at the appropriate time.”

The murder of Jan Sarens came on the eve of a major sports event that local and state authorities have been promoting for months as super-secure and a pivotal opportunity for Acapulco to regain its international image and tourism lure.

-Kent Paterson

Frontera NorteSur: on-line, U.S.-Mexico border news

Center for Latin American and Border Studies

New Mexico State University

Las Cruces, New Mexico

Articles for February 23, 2013 | Articles for February 24, 2013 | Articles for February 25, 2013

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2025 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.